McLeodganj taught Dipika much about serendipity and trusting the universe.

It was January 2013 when I first set out to meet the Dalai Lama. His Holiness lives in exile in India, in McLeodganj, a city in Dharamsala, in the clouds where the Buddhist chants are as clear as the calls of the Himalayan bulbul. It is a retreat in the perfect sense and I had just started to write my third novel, a novel I felt compelled to write because a monk who was about to immolate himself had started talking inside my head.

I had left home two weeks earlier for a series of literary festivals in India — starting with Hyderabad and ending with Delhi. I did not really have a plan for McLeodganj. I had visited Tibet in 2011 and the changing face of Lhasa, where the culture of the Han Chinese, who seemed to be wiping out the native Tibetans, had been disturbing. The road signs in Tibet are now inscribed with the rigid straight lines and flailing arms of Chinese script, overshadowing the gentle curlicues of the Tibetan alphabet flowing around the prayer bells and circling mandalas. Soon after this trip to Tibet, a Tibetan monk on the verge of self-immolation started talking in my head, incessantly, and as most writers know only too well, the only way you can silence such a voice is by writing the words down.

But I had also lived and worked in Shanghai for almost three years, mingling with intelligent and humane Chinese academics, writers and students; I could not write an un-nuanced morality tale of good versus evil about Tibet. As an Indian, I knew we had our own Sikkim (just as we now have taken Kashmir). So I was headed for McLeodganj in 2013 to make sense of this, to find a monk like the one talking in my head. A well-connected official in New Delhi had liked my debut novel, became interested in my subsequent work and offered to help with research. Over lunch at a fancy Indo-Chinese restaurant in South Delhi, she casually asked, “Since you are going to McLeodganj, would you like to see the Dalai Lama?”

Was that even a rhetorical question?

I left Delhi armed with the telephone numbers of the Dalai Lama’s chief translator and the director of the Tibetan Archives. The Dhauladhar Range came into view in the early morning of my bus ride from Delhi, lighting up the sky with its snowy cape and erasing the darkness with a warm milky glow. First, there was one white peak, then another and another, until at every turn, the view dazzled even more. Such pure whiteness as I have never seen, against the soft twinkle of the night sky, and the valley glowed with a faint light below.

It seemed like an excellent omen; I assumed I would just get into McLeodganj, find my monk, engage him in conversation, meet the Dalai Lama and be on my way. Nothing to it. Eleven days, mission accomplished. Then, I could get back to my real life, the routine of poring over books, making sense of this experience and putting it into a novel. I reached McLeodganj, checked into the Pink House, ordered some ginger honey tea and waited for the universe to deliver.

Which it quickly did. The Dalai Lama’s translator returned my call to say that His Holiness was on a retreat and would be seeing no one in the next two weeks. He would be happy to talk to me but, bad timing, maybe His Holiness would be available the next time? The proprietor of the Pink Lodge asked if I knew that there was a waiting line for years(!) to see His Holiness and that I needed to apply online. The guy at the local pharmacy told me Tibetans wait all their lives but, alas, most die before they are able to see His Holiness.

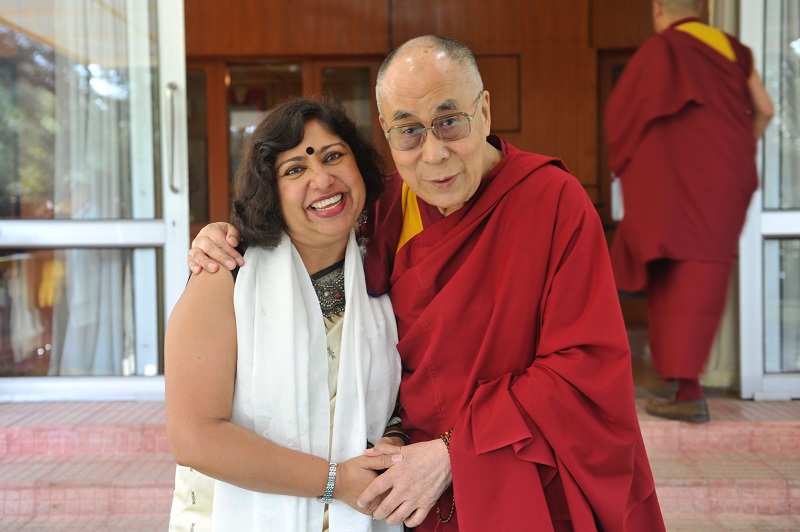

dipika_with_dalai_lama.jpg

I felt like a complete idiot. All the old insecurities — that maybe I was a writer who had stumbled into this calling with no idea of what I was doing — came rushing back. I was in the wrong profession and clearly too stupid for this.

As I walked along the empty roads of McLeodganj (it was low season), I felt completely wretched. The Tibetan volunteer associations were closed until the summer crowds returned and I had no idea where to even begin looking for my monk. It was biting cold after a slight grey drizzle and I was wearing boots.

Suddenly, a man offered to shine my dusty boots for a low price — business was so bad nowadays. “Didi,” he called out to me in Hindi. He had come all the way from Rajasthan but there was no work now. I stopped at his stand and started taking off my boots. As I bent down, I could see, behind the man, a green sign waving in the wind just below street level: “English Conversation Teachers Wanted”. It was the headquarters of the Ex-Political Prisoners of Tibet.

I could not wait. I told the Rajasthani man I would be right back and ducked into the low doorway in my socks, following the signs to the “Office”. The lone man sitting there spoke halting English and no Hindi. He had to dial someone else. I waited below the pictures of Mahatma Gandhi and the Dalai Lama. And I waited. And waited. Finally, I wandered around the building, looking at pictures of the ways in which political prisoners are tortured. There were paintings (since pictures were unavailable) of tiny thumb-cuffs used to string up men, and of women with fish hooks in their vagina. There was a list of the martyred, most of whom had barely begun their adult lives.

When I had waited for 35 minutes and was about to give up, a very dishevelled man called me in. Initially sceptical about why I was at their office, he warmed up after googling my university affiliations while I silently waited again. Tomorrow, he said, you can begin to teach Conversational English.

Over the next 10 days, I taught a group of men and women who were all ex-political prisoners who had fled from Tibet. In my class of nine, five were monks, four were not (although one among them used to be). I was their English conversation partner and so they told me about escaping on foot from Tibet, walking over the Himalayan ranges with inadequate footwear, trying to avoid the splitting ice and the strong currents in streams. When there were children, they took turns to piggyback the young ones but, inevitably, they lost some. They talked about walking through the moonlit fog-shaded mountain passes and sleeping through the warmer days. Some were lost in these passes, while the sick had to be abandoned. They were crippled by homesickness and hunger and exhaustion but always hounded by the fear of Chinese bullets.

Every day, from 4.30pm to 6.00pm, I heard their stories. Then I went to a meditation class to distance my mind from so much human misery. In the mornings, I would go to the Tibetan archives where the director would open up the ancient Buddhist texts, the Jataka Tales, that say much about the fortitude of the Tibetan people. There were beautiful murals everywhere, describing the Cycle of Life. Other mornings, I would go to the Dalai Lama’s Temple to speak to the chief translator. I wrote every day. A well of words sprouted, bursting to be free, but they were not my words; they were the stories of the Tibetans I had met going about their business in every street corner.

I did not meet the Dalai Lama. Instead, McLeodganj taught me much about serendipity and trusting the universe. About ceding control and slowing down. The day before I was about to leave, the lights went out after a relentless storm. My first reaction was, why doesn’t India ever get any better? But I was forced, in the dim light, to watch the strong winds lashing the trees, which seemed to reach out to each other, the conifers and the shrubbery, all shivering leaves in a dance of solidarity against the elements. Then a flock of kites came. At first, I thought they were in distress, wheeling in the wind with raucous cries, but then it was clear that they were riding the wind, as confident surfers ride the high waves. And meanwhile, the mountains in the background were being slowly dusted with a cloud of white, like a divine hand sprinkling powdered sugar on chocolate.

I had lived through monsoon storms in the Klang Valley but, glued to a TV or a computer screen, I usually missed Mother Nature in her glory. McLeodganj held up this Spirit of Beauty in its entire splendour, in nature as well as in the hearts of the indomitable and compassionate Tibetan people. I had thought that this journey would be about meeting the Dalai Lama but it turned out to be a larger connection with ordinary Tibetans, whose stories needed to be told.

“Maybe you’ll meet the Dalai Lama after your book is published,” said the director of the library. “One person blows up a building and the media has pictures everywhere, but our youth are burning themselves and no one cares. Please tell their story.”

On Sept 4, 2015, two-and-a-half years after I had first set out on my quest, I met His Holiness the Dalai Lama. By then, I had started to tell the Tibetan stories and McLeodganj continued to call me. McLeodganj, in just 11 days, first taught me the truism of the old cliché — it is the journey, it is all about the journey. We all have the same destination in the end, no matter what lives we live.

An earlier version of this essay appeared in Chicago Literati (Wanderlust Issue, August 2014).