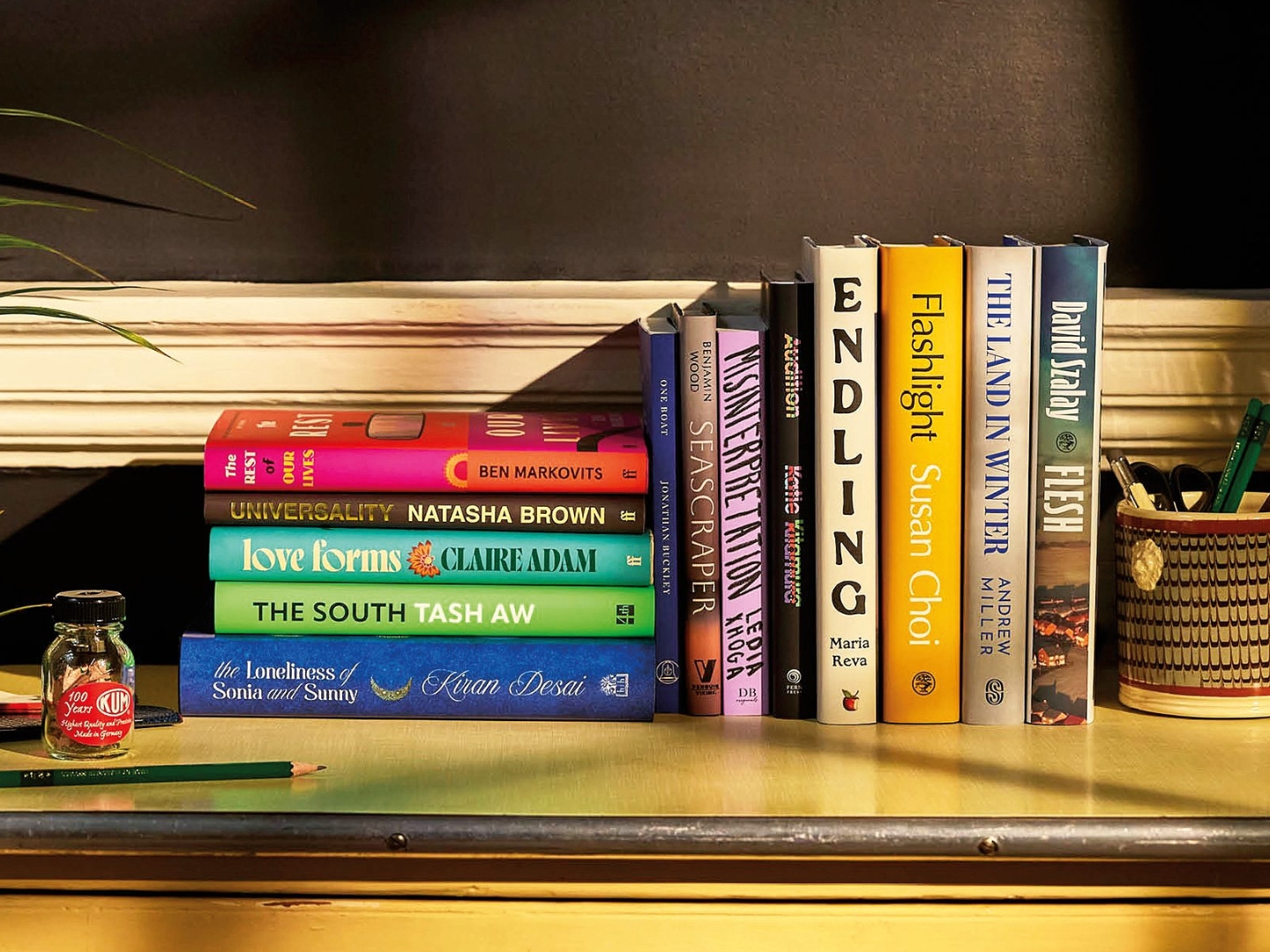

The 13 longlistees were chosen carefully from an original cast of 153 books (Photo: Booker Prize Foundation)

Intensity seems to be the flavour of the year in the longlist for The Booker Prize 2025 revealed on July 29: potent, character-driven introspections that fixate, with brilliant literary deftness, on the human identity’s most defining influences. Immersive moments of slow, poignant realism, desperate and fiendish desire and the pursuit of happiness buffed by inescapable adversity evidence a stirring (and very much needed) embrace of the bold and raw in a modern age where life seems to be dictated by forces beyond our control.

The selection, notes chair of the judges Roddy Doyle, had been thoughtfully and affectionately graded over seven months, distilled from an original cast of 153 books. The 13 longlistees comprise a cosmopolitan crew of short and long novels which, in Doyle’s words, “are all alive with great characters and narrative surprises” and “examine identity, individual or national”.

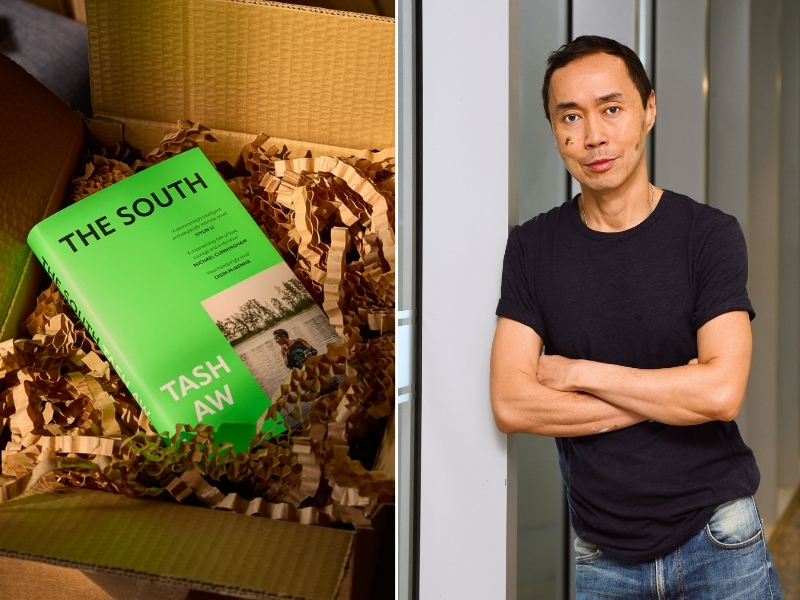

Malaysians can enter our independence month with extra pride knowing that among these acclaimed works sits The South by celebrated local novelist Tash Aw. Published earlier this year as the first in a quartet, his take on the Asian epic sheds the arrogance of sketching a holistic history, favouring instead an episodic chronological layout that lends microscopic nuance to its cast of characters: adolescent boys Jay and Chuan are eager to discover more about themselves and their futures, each guided by their inherited histories and surrounded by increasingly complex portraits of their parents.

The author’s elaborate palimpsest of time earned his book high praise, particularly when coupled with the families’ entanglements over the farm and the wealth and ownership it symbolises. This intergenerational tale is riddled with longing, anticipation and emotional teleology — one teen is compelled to mourn for his memories as they happen while another hones in on the moment, all while a looming economic precarity rips Aw’s literary Malaysia between rapid modernisation and lost history. “To call The South a coming-of-age novel nearly misses its expanse,” say the judges. “This is a story about heritage, the Asian financial crisis and the relationship between one family and the land.” Aw is the second Malaysian to be longlisted for the prize three times after Tan Twan Eng.

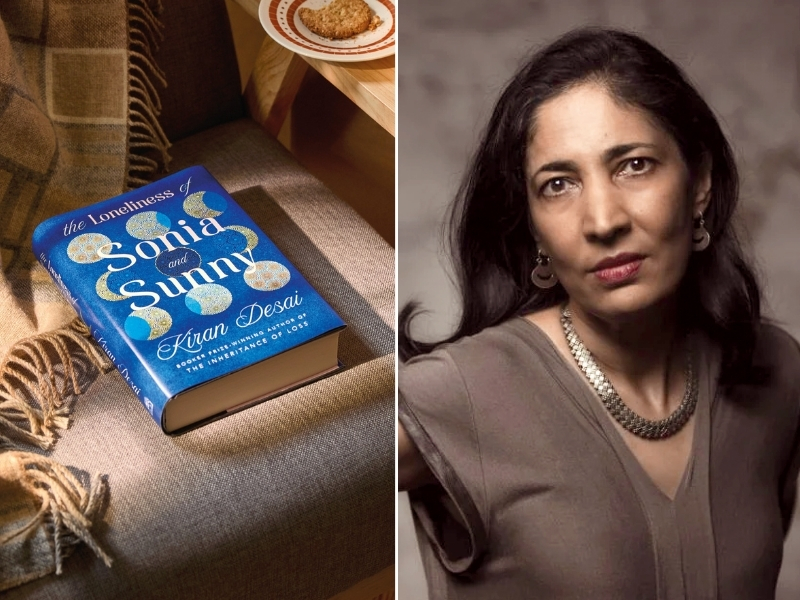

Indian author Kiran Desai returns to the nominees list for the first time in 19 years, when her book The Inheritance of Loss won the Man Booker Prize (as it was then known) in 2006. Her 700-page tome, The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny, reflects on the sweeping romance of its central couple, two modern Indians living in the US, situating their growing, precious relationship within a tumultuous nexus of family history and clumsy matchmaking that is just as important as the love story at play. Desai’s narrative is devastating and dramatic, invoking a conversation on fate and uncertainty that spans the protagonists’ lives.

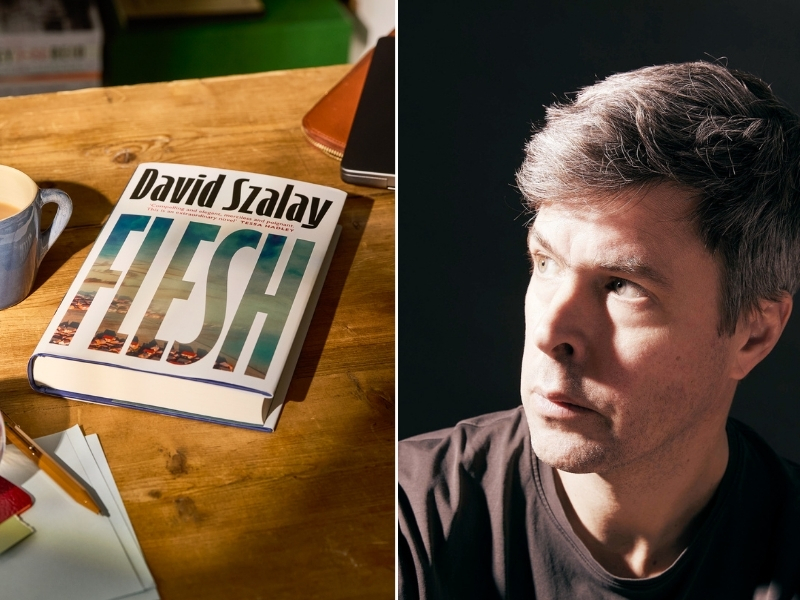

Indeed, at the heart of many of this year’s nominees, one finds the push and pull of autonomy and helplessness. Across nations, cultures, times, ages and classes, several authors pull the individual struggle against life’s intangible circumstances into focus. David Szalay’s Flesh tells the hypnotic, existential tale of István, a passive Hungarian man dragged around and tossed about by the events that surround him: an affair in his early life, time in the military, the fluctuating global economy. Szalay’s portrayal of detachment gives him surgical control over the more brutal moments penetrating this novel on what makes life worth living.

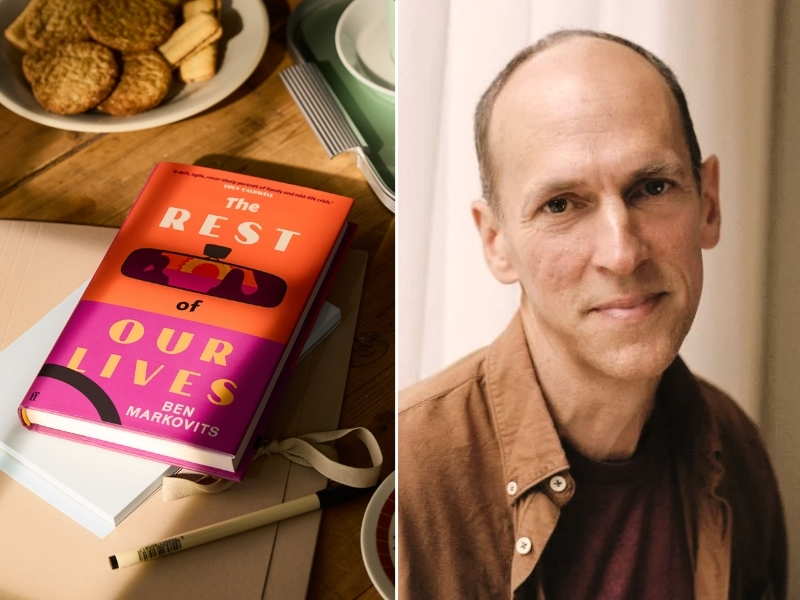

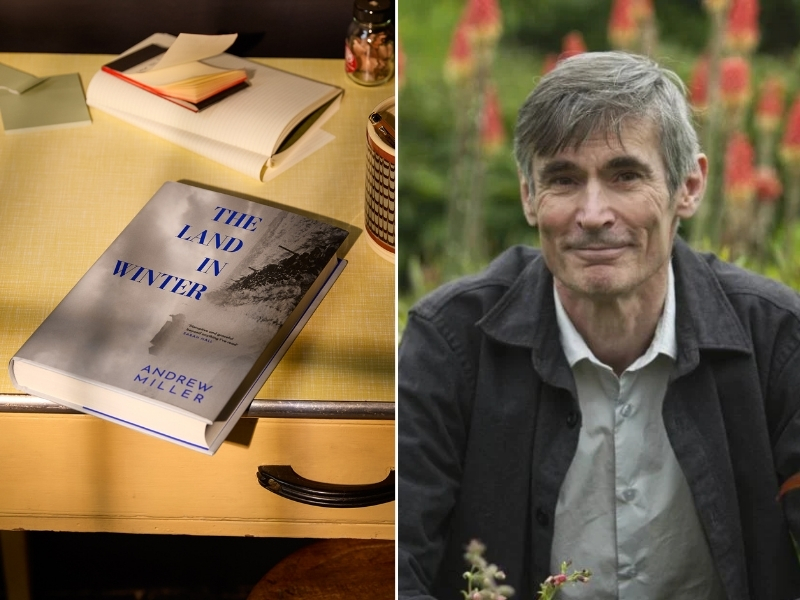

Meanwhile, The Rest of Our Lives by Ben Markovits and The Land in Winter by Andrew Miller are concerned with surrender in their own ways. Markovits’ warm story stars a man who promised to leave his wife once his youngest turned 18 on account of her past infidelity. When the time comes, he embarks on a road trip of self-discovery, questioning his will to escape. Miller, on the other hand, casts us to post-war Britain, where two married couples’ seemingly regular lives in the countryside thinly veil an underlying discomfort and awkwardness with who they used to be and finding bonds between themselves.

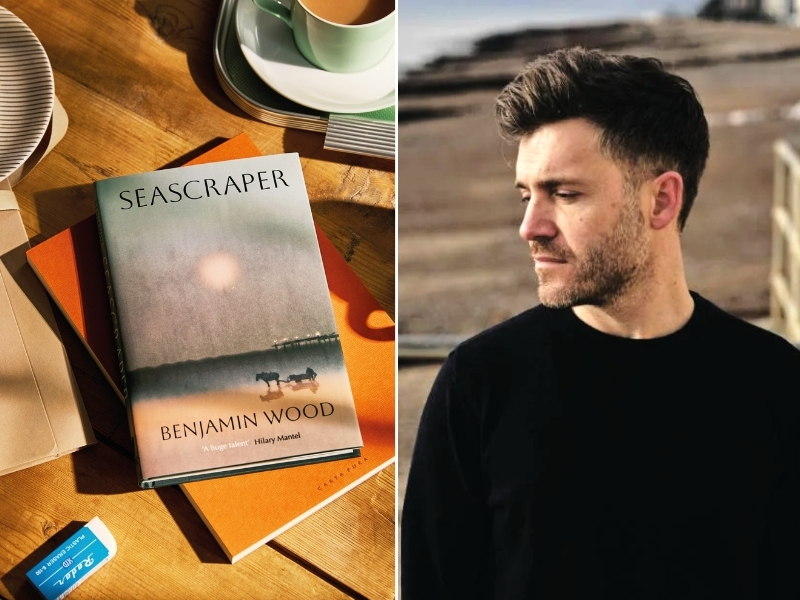

Benjamin Wood’s work suggests a similar preoccupation with vicissitudes and haunting pasts. Seascraper is led by 20-year-old Thomas, aged beyond his years by the daily toil of gathering shrimp on the beach. He accepts his monotonous life with resignation, a quiet ritual of cigarettes and hard labour from which the only solace is his guitar. We sympathise with his innocence, the silent frustration of wanting more — a wish that seems more feasible when Hollywood director Edgar Acheson comes to town — but come to root and fear for him in equal measure as he attempts to find his place in the world.

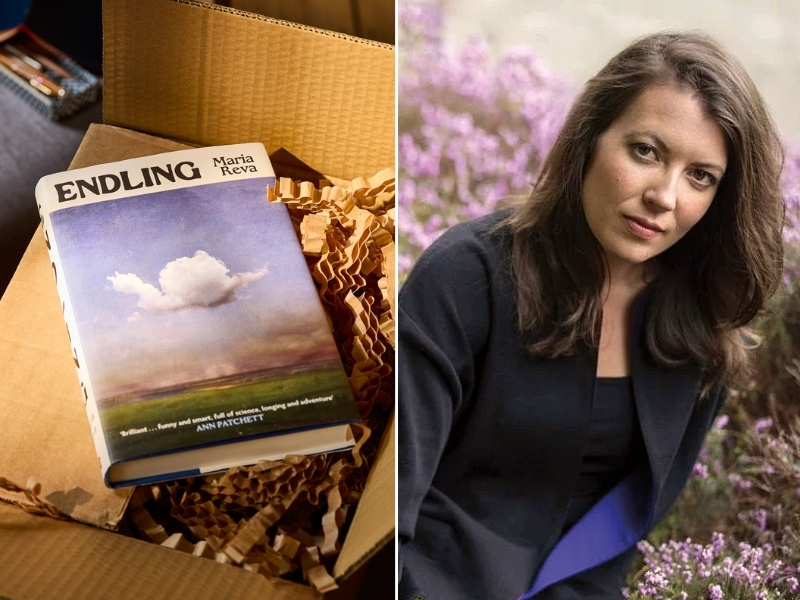

Ukrainian-born Canadian writer Maria Reva handles this anxiety in a more urgent contemporary context through her witty yet shocking debut novel Endling. Set in 2022, Yeva conveys a contemptuous indifference towards the “romance tours” through which she earns money, but is happy to clock in hours as a party filler for an agency promoting mail-order brides to Western tourists. Her true love is caring for endangered snails, spending her paycheques on new equipment for her mobile gastropod laboratory. The Booker Prize judges note, “Endling shouldn’t be funny, but it is — very. It examines colonialism, old and neo, the role of women, identity, power and powerlessness, and the very nature of fiction writing.”

Reva’s skilful rendering of exhaustion through her jaded protagonist picks up when new characters plan a heist to kidnap the foreign bachelors and expose the unethical patriarchal industry — only for the whole book to be blown into metafictional ruin by Vladimir Putin’s real invasion of Ukraine. Guilt, self-awareness and anxiety from the author’s persona enter Yeva’s story, and the alignment of the endangered, unpopular little creatures with the threatened and neglected lives in Ukraine becomes painfully clear.

This year also marks one of the more diverse judging outcomes in recent years, with nine represented nationalities, though UK authors secured the highest number of nominations. “[The list] champions global perspectives. The stories are set all over the world,” comments Booker Prize Foundation chief executive Gaby Wood. “Many of the novels speak to the reader in an unadorned, confiding voice. This intimate effect, so difficult to achieve, was immediately appreciated by the judges, who are as alive to unshowy skills as they are to more virtuosic ones.”

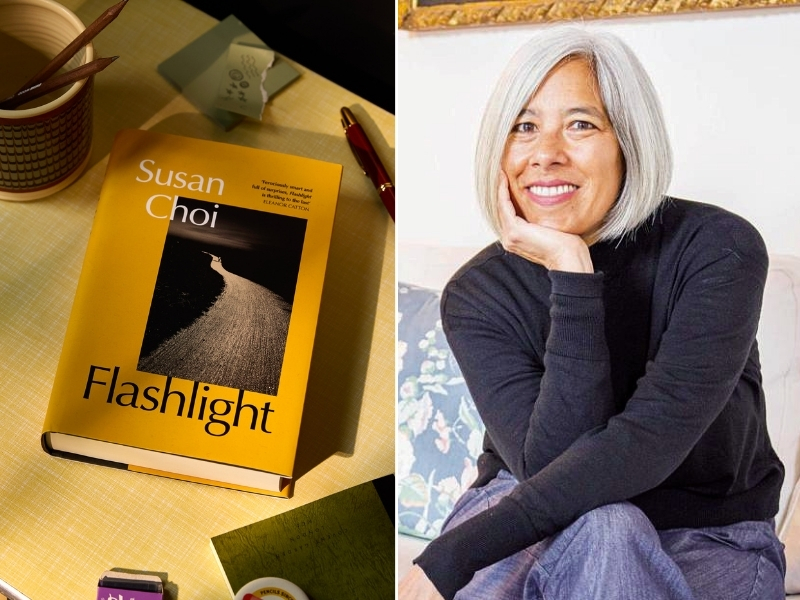

Susan Choi’s Flashlight exemplifies this engaging, vocal, geopolitical power. Its lead, 10-year-old Louisa, loses her father in a mysterious accident, but rather than grieve, she is unwieldy and indignant. As the truth unravels, Choi traces the historic tensions between Korea and Japan and the challenges of displacement and immigration (recalling her own family’s past) to suburban America and the North Korean regime in this rich and profound investigative saga.

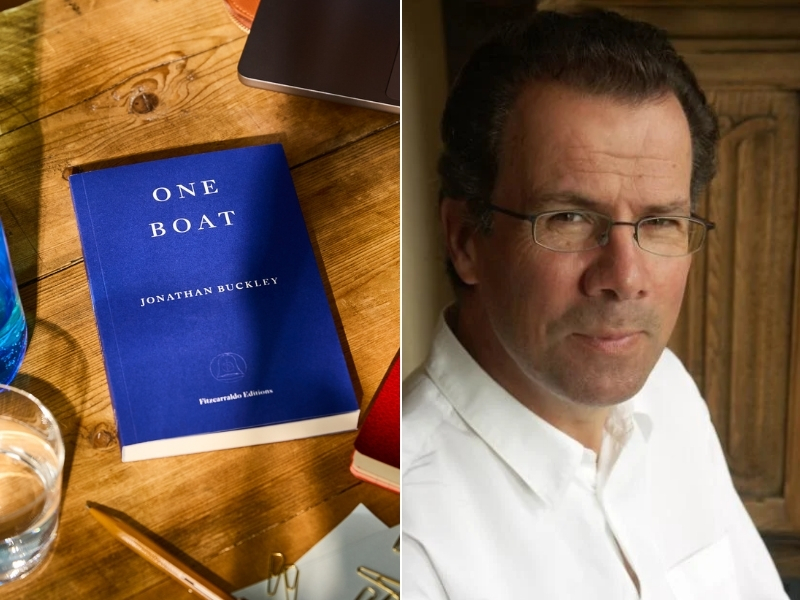

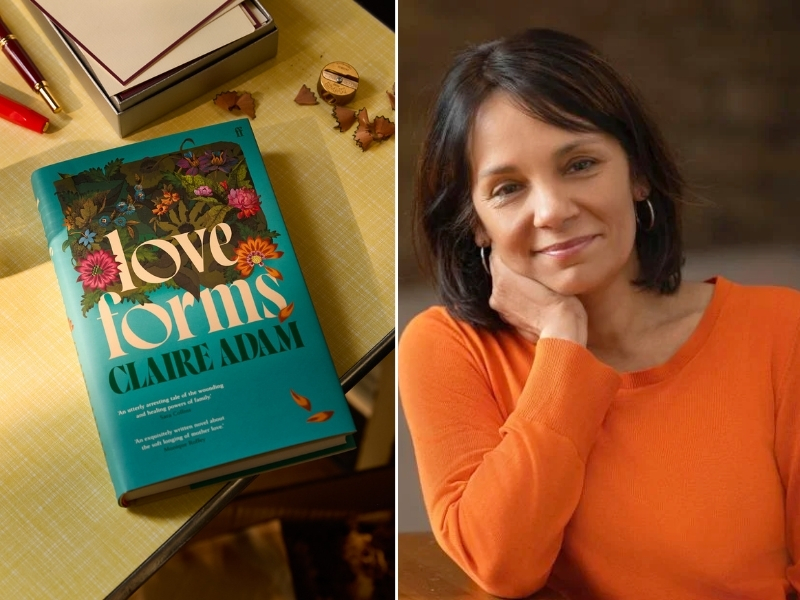

Jonathan Buckley’s protagonist in One Boat, the lawyer Teresa, has also lost her father, but is more absorbed in thought than fury. She visits a coastal town in Greece for the second time — the first was to mourn her mother — now to grieve her paternal loss while surrounded by past encounters. Packed with unique personalities and intricate insights, One Boat “raises questions about grief, obsession, personhood and human connectivity”, said the judges. Trinidadian Claire Adam also tackles loss and family in Love Forms, a hushed and heartbreaking rumination on lost possibilities which follows a woman’s unrelenting and painful search for the baby she gave up at 16 in Venezuela through an unflashy, reflective and beautiful voice.

On the more satirical end, Natasha Brown’s comedy thriller Universality pokes at the dominant systems of media and politics by drawing attention to the inherent weight of language and rhetoric. The opening case of a man bludgeoned to death with a gold ingot spurs an eager journalist to solve the case. Her viral magazine feature forms the story’s top half, before unveiling a series of accounts from multiple perspectives where the blurring of integrity and entertainment becomes louder. Just as the murderer Jack wonders how one can hold so much “value” in his hands with a gold bar, readers must consider the heft which the book they are grasping holds. Words are your currency, Brown reminds us.

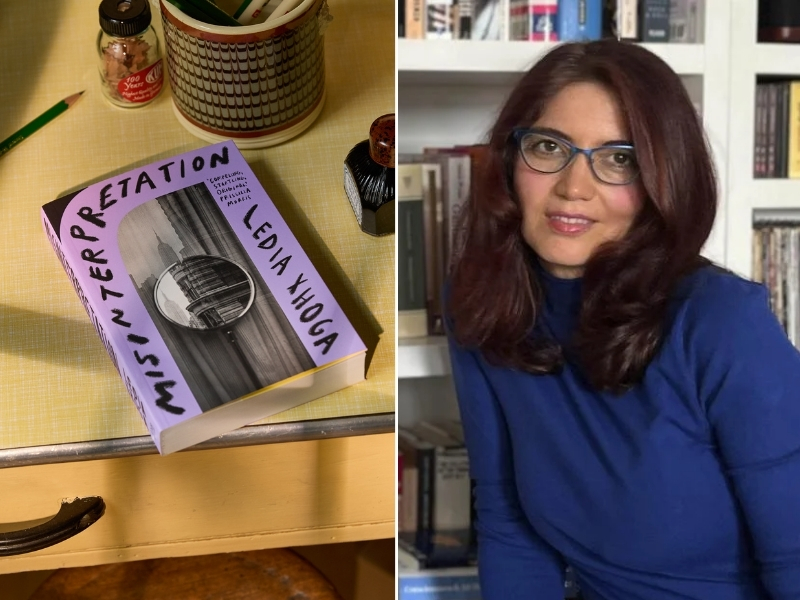

Misinterpretation by Albanian writer Ledia Xhoga (the second debutante on this list) contemplates language in a darker setting. A Kosovar torture survivor requests an interpreter, a nameless Albanian woman, who agrees reluctantly. Over time, she grows enmeshed with her client’s struggles — she has been known to become overly involved in the lives of the immigrants she helps — throwing her marriage into chaos and stirring up buried memories. Xhoga lays out issues of alienation and privilege, scaffolded by external expectations, failed communication and the tenuous line between help and harm.

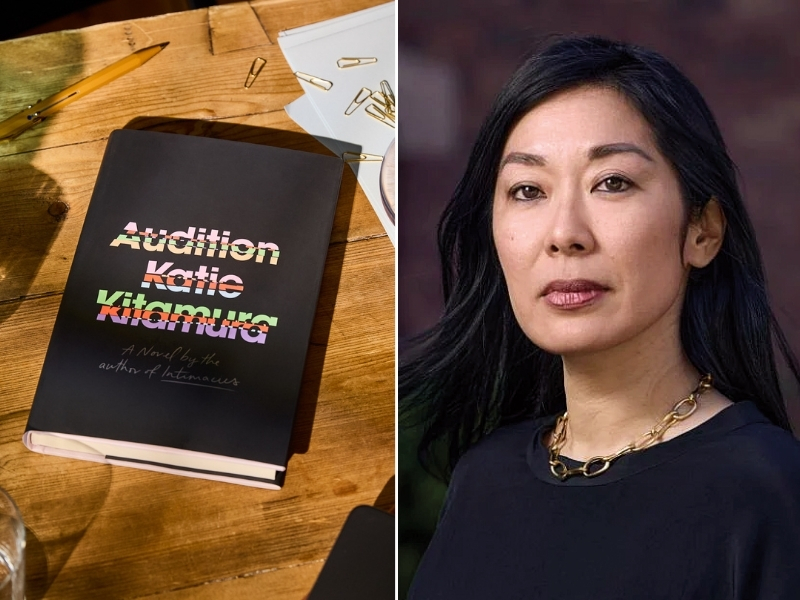

The unreliability of words reaches its peak in this final nominee, Katie Kitamura’s Audition, an extraordinarily constructed and destabilising book that starts with an actress meeting a man for lunch, wherein the truth surrounding their relationship is precariously and disturbingly presented for readers to interpret. Some critics seemed unhappy with Kitamura’s lack of detail, the brazen backtracking of its drawn out opening timeline, frustratingly bloated by directionless mystery. But others, including the judges, relish the Japanese-American novelist’s minimalism, combining frank prose with zoomed-in psychological insights to yield an unsettling interpersonal puzzle that exemplifies Kitamura’s distinctively concise style.

The Booker Prize 2025 shortlist will be announced at a public event on Sept 23 and the winning book will be unveiled on Nov 10.

This article first appeared on Aug 11, 2025 in The Edge Malaysia.