The Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana, designed in 1938

We, my friend Mark and I, have just come home from a visit to Italy. It’s not our first trip there, and neither were we strangers to the cities of Florence and Rome. Repeat visits allow a freedom unburdened by expectation. We looked forward to this kind of luxury that familiarity brings, a familiarity that opens up more time and space in the mind to think about things at a slower pace, to ponder and daydream.

We had planned to arrive in Florence to coincide with Free Museum Day, which falls on the first Sunday of every month. Italy opens up its state museums gratis under an initiative called the Domenica al Museo by the Italian Ministry of Culture, which aims to make the country’s cultural heritage accessible to everyone. European museums are fascinating because they offer a window to how the powerful perceived the world and that, in turn, shaped the aesthetics of a culture. I make it a point to visit at least one museum each time I am in Europe to enjoy the beauty and grandeur of the collections. By simply walking through them, I gauge how my own perceptions of beauty, power and patronage are formed.

Our first stop was the Uffizi Gallery. The paintings are from the personal collection of the Medici family, a powerful banking and political dynasty that controlled Florence for a significant period during the Renaissance. They had built the Uffizi in 1560, setting up administrative offices on the ground floor and using the upper floors to house their art collection. Here, in these artworks, we can appreciate some of the highest artistic achievements of the Renaissance. Among the many artists they supported were the familiar names of Michelangelo, Raphael, Leonardo da Vinci and Botticelli.

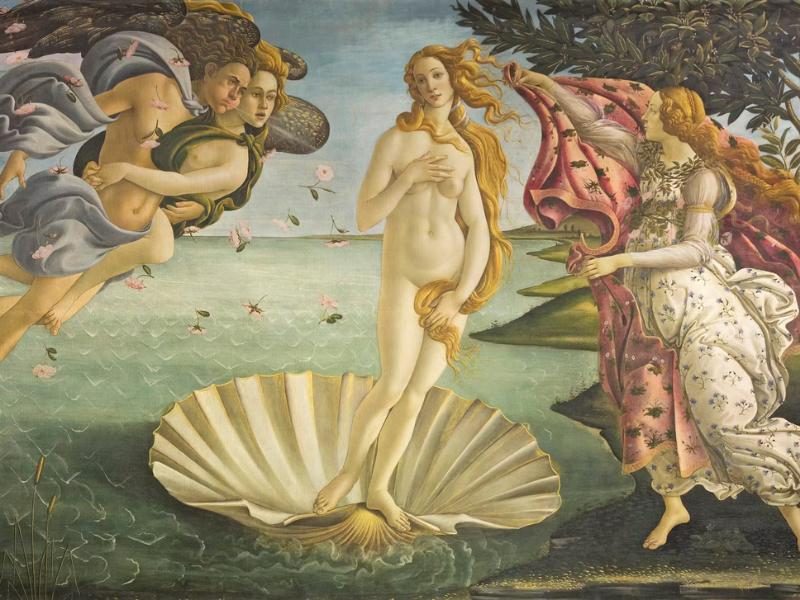

We arrived shortly before the doors to the museum opened and were greeted by a long queue. We wanted to see the Birth of Venus, painted by Sandro Botticelli between 1482 and 1485. It’s a painting said to embody the essential humanist ideals of the renaissance — a subject matter inspired by Greek mythology depicting a nude form surrounded by wind, a shell, waves and flowers.

body_pics.png

We were determined to stay focused and immediately proceed towards the room where the Botticelli was hung. Once inside the Uffizi, however, we were swept along with the crowd and just flowed through gallery after gallery of paintings. It was not long before my eyes started glazing over at the opulence of the setting and the scale of the collections. How much power and wealth did a family need to have in order to amass that many artworks of such fine quality?

When we finally arrived at the Botticelli, what struck me first was how different it appeared from the images in the stamp-sized slides I stared at in my college art history classes all those years ago. The painting was much bigger, and the colours were brilliant and luminous after a 1987 restoration. The details of the flowers and waves stood out for their lightness. Botticelli’s other painting in the Uffizi — La Primavera, painted earlier between 1481 and 1482 — was similarly rich in colour and detail and equally as jaw-dropping.

My amazement at the difference between seeing artwork as reproductions in slides and art books, and seeing them “in the flesh” would play out again when we went to the Accademia later to see Michelangelo’s infamous David, created between 1501 and 1504. The sculpture was stunning in its monumentality, in the buttery surface quality of the marble and in the high level of detailing achieved in depicting musculature. I couldn’t help but wonder if I would have been similarly struck by these works of art had I not first encountered them as reduced-sized images, pre-restoration, with blurred details, not to mention the many inaccurately coloured variations in art books and later images on the internet? The way ideas and images are presented in the course of one’s education dramatically skews how we view the world. But these OMG moments of realisation offer opportunities for relearning and keeps curiosity alive, thus enriching a life-long journey of educating oneself.

1.png

Part of the Uffizi experience these days also includes, of course, navigating the crowds that in equal parts are looking through their handphones at the painting, and at the painting itself unmediated. Not to mention the fact that in this day and age, it is also necessary to document what we have seen and done, and as a process of verification, post requisite images on one of the many social media platforms to affirm the reality of one’s experience. A tip: by the time we left the Uffizi by late morning, the snaking queue to enter the museum had dissipated.

We thought we would do something outside of the many recommendations by the army of bloggers and vloggers, to see a part of Italy’s capital often bypassed by tourists and in contrast to the plentiful lush baroque expressions all over the city, which of course was meant to show off the grandeur and power of the Catholic Church. Hence, our arrival in Rome at the iconic Termini Station after a scenic train ride on Trenitalia from Perugia.

The original train station was torn down and rebuilt in 1937 during Benito Mussolini’s dictatorship as a modern gateway to the 1942 World’s Fair which, interestingly, never happened because of WWII. Likewise, Rome’s business district, which is often referred to as the EUR (Esposizione Universale Roma or Rome Universal Exposition). Both these projects were halted in 1943 only to be continued after the war.

Today’s Termini Station is updated and modernised. The earlier Mussolini-era renovation by the architect Angiolo Mazzoni can be seen along via Gioletti where the intercity busses stop. We walked into the Mercato Centrale, a food court converted from its original intended use as the station’s main dining hall — not to eat primarily, but to gawk. The epic interior with its monumental marble chimney known as the Cappa Mazzoniana after the architect Angiolo Mazzoni, was our first encounter with Fascist-era architecture close-up.

2.png

The EUR was also meant to be a show of strength, but this was a different kind of power. National Fascist Party leader Benito Mussolini, or Il Duce, had a vision for the future of Italy, and he expressed it by championing an architecture that drew inspiration from the monumental constructions of ancient Rome. Mussolini had intended for the EUR to be a showcase celebrating Fascism’s success at the World’s Fair. Today, it is a thriving business district that is home to an array of restaurants, museums, banks and Italian ministry offices.

My first impression of the EUR was how reminiscent it was of Giorgio de Chirico’s metaphysical paintings of the early 20th century. Repeated colonnaded walkways, broad straight boulevards, spacious but empty piazzas. It was dreamlike, strangely still and silent. There were parked cars, restaurants, museums, but hardly anybody on the streets save for a group of school children crossing the road. Its silence and austerity contrasted sharply with central Rome’s noise and baroque excess.

We spent a fair bit of time at Palazzo della Civilta Italiana, or the Palace of Italian Civilisation, designed in 1938 by three architects: Giovanni Guerrini, Ernesto La Padula and Mario Romano. At the top of the building, an inscription read: “A nation of poets, of artists, of heroes, of saints, of thinkers, of scientists, of navigators, of migrants”. This is a quotation taken from one of Mussolini’s speeches. The arches on the ground floor framed sculptures representing industrial workers and tradesmen rather than saints and wealthy patrons, which I was thought quite beautiful and meaningful. By giving order, stability and a vision to a nation wrecked by the effects of WWI, it is not difficult to see how he was able to capture the hearts of Italians of that time.

3.png

Growing up, I was taught simply that Mussolini and Fascism were bad news for the world. Standing there in front of the palazzo, it seems like, between good and bad, there is also much that is grey that lies in between. The Palazzo is used today as headquarters for fashion brand Fendi.

The Italians are mindful of their past and demonstrate a healthy acknowledgment of the course of history as evinced in the careful restoration of their architectural heritage. Regardless of one’s stand on historical developments, the preservation rather than eradication of the material residue of an era allows space for continuous discussion and evaluation of the past.

For me, to be able to physically be inside spaces I have only read about or seen through other people’s eyes pushes home the point that although history may be written by the victor, there is more nuance in civilisation than meets the eye. Truth be told, I don’t know much about Fascism, or about Mussolini, but I’m finding what I experienced to be quite fascinating. After food and drink, this for me, is one of the most important reasons to travel: the encountering of instances that open my eyes to the incompleteness of education. For now, there is much homework and reading up to do, well before the next return to Italy.

This article first appeared on Jan 5, 2026 in The Edge Malaysia.