From left: Zain Azahari Zainal Abidin, his wife Zainun Jamaluddin, son Azmir Zain and daughter-in-law Haslinda Hussein (Photography by SooPhye)

The number 60 is especially significant for art collector Zain Azahari Zainal Abidin this month. On Jan 6, he celebrated six decades of marriage to Zainun Jamaluddin. They wed in 1962 when he was 27 and she,25. Among their wedding presents was a small watercolour titled Batu Caves by Syed Ahmad Jamal, given to Pak Zain by an ex-classmate. It was the first piece in the Zain Azahari Collection, which started then and today encompasses several hundred artworks, housed mostly at the family’s private Galeri Z in Kuala Lumpur.

To mark the milestone celebrations, Zain Azahari’s youngest son Azmir and his wife Haslinda Hussein thought it fitting to put together a book featuring 60 works from his father’s trove, covering as wide a period as possible, with accompanying write-ups that relate just a few of them to the family’s own history, while the rest highlight various aspects of the country from Merdeka to the present.

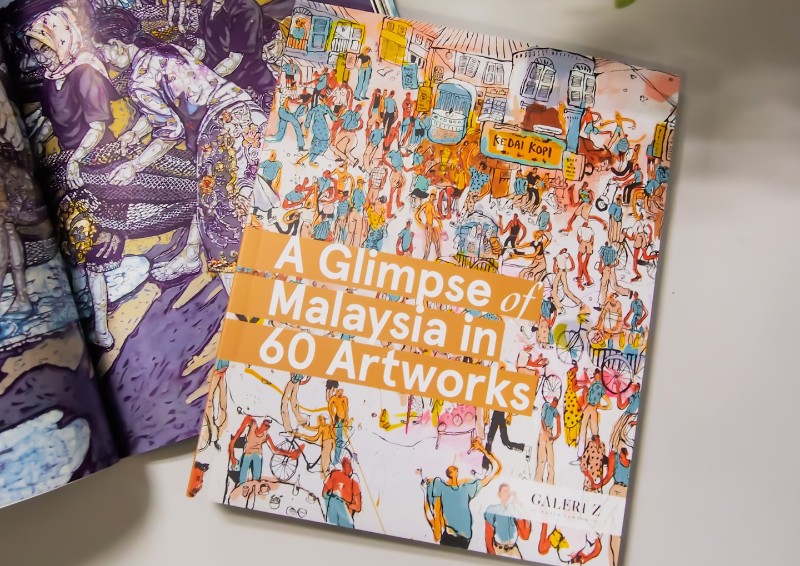

A Glimpse of Malaysia in 60 Artworks is bookended by Khalil Ibrahim’s 1957 oil painting, Kampung Scene, and Umibaizurah Mahir Ismail’s 2020 mixed-media installation, Please Use Me, about the pandemic. The aim is to emphasise how “Malaysian art is a record, a documentation of the country”, Azmir says. It speaks of our history and culture (such as traditional healing, feng shui, Indian classical dance, Malay folk tales and mysticism) as well as incidents and issues tied to politics (the communist insurgency and May 13), the environment and Malaysia’s Hindu-Buddhist origins, among other things.

The country’s unique history is the result of its geography — it is at the middle of the sea route between two ancient civilisations, India and China — and abundance of natural resources, which attracted the Europeans, and what has happened here over the centuries, he adds.

“My family is a product of migration. Mum’s side is from Sumatra; generations from my father’s side have lived here but one branch is from Sri Lanka and another, Yemen. Today, my IC says I’m Malay. It’s kind of ironic, right? What this book is trying to say is that a large chunk of the country is actually the outcome of Malaysia’s migratory history. As a consequence, our art is unique and very distinct.”

_s1a9065a.jpg

Looking back to the 1930s, when his parents were born and the British were still the colonial masters, and then the Japanese invasion and WWII, he reckons the idea of an independent country, self-rule and being masters of your own destiny was a very big thing for Pak Zain’s generation.

“For my father, consciously or otherwise, his collection serves as a reinforcement of belonging to this land, an assertion of nationhood. We are aware the pieces, including those we acquired in the last 10 years, mean a great deal more to my parents, dad especially, than pretty things to decorate our walls.

“As the sibling who takes care of the artworks, I thought, ‘Why don’t we document the stories behind some of them?’ I didn’t want to talk about our family life, but I felt that the pieces were interesting and spoke of different periods of the country — you can see the evolving tastes of people from pre-Merdeka.”

Narrowing his selection to 60 works was no mean task for Azmir, who had accumulated stories about the collection from conversations with Pak Zain and many of the artists themselves and reading about their work, apart from a personal interest in art since his days as a law student in the UK. A lot of the works have been with the family for decades — he pinpoints three that have a special nostalgic meaning for his parents.

wedding_photo.jpg

Chuah Thean Teng’s batik Kampung Life, one of the first works Pak Zain acquired during the 1960s, is imprinted in Azmir’s mind. “If you look at our old black-and-white family photos, you can see it in the background. Even when I was a child, I remember spending time playing with toys or doing work near a wall where this painting was hung.”

Hoessein Enas’ Kerbau resonates with his parents because it reminds them of the old days when Malaya had a deep agricultural history. Their generation valued hard work and it was honourable to toil on soil and to be seen doing it. The oil painting represents the whole concept of rezeki and feeding the family, Azmir explains.

Another favourite Pak Zain particularly values is Latiff Mohidin’s Pago-Pago II, which he bought in 1966/67 for RM150. “He was relatively new to the legal fraternity then and that was a large sum for a junior lawyer.” In 2018, Centre Pompidou in Paris requested that the painting be displayed as part of Latiff Mohidin: Pago Pago (1960-1969) — the first solo show at the French museum by a Southeast Asian artist. Apart from its remarkable journey, this prized work marked the beginning of a friendship between the collector and painter/poet that has deepened over 50-plus years.

Azmir does not name his mother’s favourite pieces but says she definitely played a role in building the collection. “Mum has always been very careful with money. Her prudence and management of the household basically freed up dad to go out, do his work and set up the law firm [Zain & Co]. That was my mum’s very prominent contribution to the whole thing. Dad also essentially saved up enough to put food on the table and perhaps acquire one or two artworks over the years.”

1965_-_hoessein_enas.jpg

Azmir was mindful that his essays on each piece should be written in concise, simple enough language so people would not be put off from reading about art. “I wanted to ensure the works are explained in a manner consistent with the artists’ intentions and the reader can relate back to them, in terms of the country’s history.

“Art needs some experience and study of, to a certain extent. But it is something anyone can appreciate; at the most basic level, you just like to see a pretty thing. Of course, you can also appreciate it from the story the work conveys. Art as a formal subject has only existed slightly longer than Malaysia as a nation has. We want to make the point that art is really for everyone and not necessarily about something overly complicated.”

Azmir, who previously worked in national institutions within the investment and regulatory fields, says lockdowns that chained him to the desk at home gave him time to research and write. Haslinda helped to curate the book and “test-read” the text in terms of its appeal, language and consistency before they got an editor to have a look.

Contemporary artist Kide Baharudin’s charming Khabar Dari Pekan graces the cover of A Glimpse of Malaysia. Inspired by stories his parents tell of a time when people respected each other’s differences, the 33-year-old painted “a noisy, unkempt town centre of shophouses and food stalls; happy-go-lucky townspeople of all races and walks of life converging to meet, drink, smoke, gossip, banter and go about their daily errands; coffeeshops, barbers, general stores co-exist side by side with alcohol traders and resthouses”, Azmir writes.

“I guess the book is also aspirational — it is not trying to preach but does try to say that beneath all the ugliness we keep seeing these days, there’s actually a very beautiful country that has a certain resilience, a certain mood and spirit which would appeal to everyone here. We thought Kide’s painting captures that.”

_s1a9054_son.jpg

Azmir, who “cannot hold a brush” but is a collector himself, notes that the current crop of artists, especially the younger ones, are not afraid to speak out or project their own voice through their work. “We have a lot of social commentators out there. Some are quite forthright in their views. That is the spirit many of them carry within themselves today.

“I think so long as they remain true to their voice, so long as there is no attempt at self-censorship or any attempt to silence the art community, Malaysians will find a great deal that can interest them in terms of what artists produce visually and what they narrate, the ideas and stories they convey through their work.”

Malaysian art has every chance of appealing to everyone, he believes, because of its subject matter and the many very talented artists here. “Part of my regret was not being able to include more of them in the book.”

Azmir is the designated director of Galeri Z, managed by the Zain family office, a responsibility that has its rewards — more conversations on art with his father. They discuss shows, what they like or do not, the artists’ motives and intentions and how they compare to those before them.

“Dad has lots of experience, having followed art since the 1950s, and collected since the 60s. So it’s very nice to get downloads and advice from him.

“When I told him about this book, he thought it was very nice of us to take the trouble for their 60th anniversary. But he preferred not to be consulted in its production because it is meant to be a gift, a surprise. I like to think my parents were touched by what they saw and liked what was written in the book.

“One of its intentions is to help build a more tangible bridge between my parents’ generation and mine, and the next generation — my own children, nephews, nieces and, hopefully, their friends.”

Is art an instant bond between father and son then? “I suppose so,” Azmir says.

Chronicling a country

For those who are of the same age as the nation, or older, A Glimpse of Malaysia in 60 Artworks affords an opportunity to flip back the years. For those born much later, it can be as a colourful introduction to people, events, policies and concerns that have shaped this place we call home.

The 60 works selected by Azmir Zain capture how the artists viewed what was happening around them and their interpretations of issues dominating the news. The author expands on these individual views with acute comments on threads — historical, cultural and political — knotted to milestones and change as the country grew.

Every painting tells a story, even as the media used evolved. Azmir includes interesting details on the artists themselves, who observed old ways of life making way for development; careless destruction of the natural environment,resulting in threats to wildlife (Warning! Tapir Crossing I by Ahmad Shukri Mohamed); the economic boom and wealth disparity; shifts in the balance of political power; government control and public retaliation; corruption; tradition and expectations of women (Hantu Tetek; Nadiah Bamadhaj).

Ismail Mat Hussin’s Untitled batik work salutes fisherfolk whose hard lives were exemplary. He was born in 1938 in Kelantan’s Pantai Sabak, where invading Japanese soldiers landed on Dec 8, 1941.

book.jpg

Fellow Kelantanese Nik Zainal Abidin Nik Salleh, who worked as an illustrator at Muzium Negara, drew inspiration from the wayang kulit to paint detailed pieces of that art form over four decades. His home state banned performances of dikir barat, mak yong, menora and wayang kulit in 1991, claiming they are heretical and propagate polytheism, but loosened the ban on the mak yong in 2019. “Nik Zainal faithfully lived his life as a Muslim and did not seem to have regarded the wayang kulit’s links to Hindu mythology as a threat or form of dilution to his own religious beliefs,” Azmir writes.

Cheong Laitong won a competition to decorate the façade of the new Muzium Negara and his panoramas of Malayan history and culture still adorn the exterior of both wings of the building.

One and the Same Thing by Ibrahim Hussein was painted in 1974, four years after the May 13 riots. Struck by TV images of Kuala Lumpur aflame, Kedah-born Ibrahim did a series of works centred on that dark period in the country’s history. One of them is the iconic May 13, 1969, which showed the image of a Malaysian flag painted over in black.

Sharifah Fatimah Syed Zubir, among the pioneering batch of the Faculty of Art and Design at MARA Institute of Technology, was the school’s finest student at its inception. MARA has come under fire for its slack financial discipline and management, Azmir notes, but deserves credit for producing a large cadre of accomplished artists.

1968_-_nik_zainal.jpg

Gan Chin Lee’s Allamanda references the New Villages set up under the Briggs Plan during the Malayan Emergency (1948-1960) while Kok Yew Puah’s For Sale reflects the country’s rapid economic growth before the 1997 financial crisis. Fawwaz Sukri’s Bawang Putih Bawang Merah Merah, a series that takes its name from the 1959 film, whisks viewers back to the heyday of Shaw Brothers and Cathay-Keris, during Malaya’s golden age of cinema. Umibaizurah Mahir Ismail’s colourful sanitiser containers in Please Use Me are a reminder about personal hygiene.

Azmir keeps the Zains’ family lives private but three paintings in the book allow readers quick peeps that pique. The Leaning Tower of Teluk Anson in Anisa Abdullah’s artwork is 250m from the post office above which Pak Zain was born. Azmir admits a personal affection for Mastura Abdul Rahman’s warm Interior 1989 because it triggers thoughts of his mother’s old childhood home in Chemor, Perak. A Song for Zain Azraai by Jolly Koh was painted in remembrance of his flamboyant, equally art-loving uncle, Malaysian ambassador to the US (1976-83) and the country’s permanent representative to the UN until 1986, who died in 1996.

This article first appeared on Jan 10, 2022 in The Edge Malaysia.