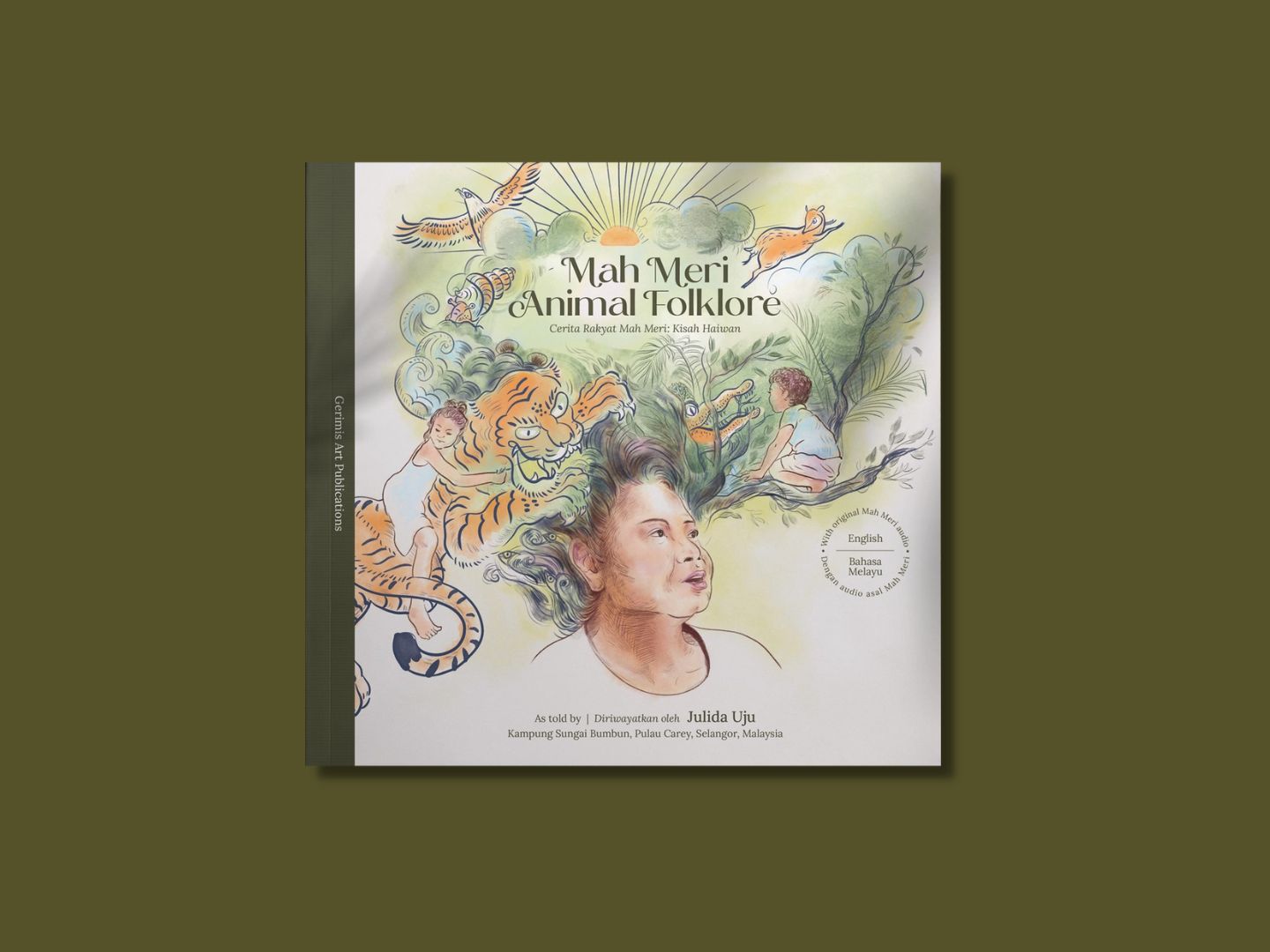

'Mah Meri Animal Folklore' is a collection of seven tales as collected by Julida Uju (Photo: Gerimis Art Project)

Everyone is looking at climate change and talking about sustainability and healing the earth. My answer to that is, listen to our indigenous people. They have the answers. They have been caring for the land for many generations and know there are certain things they can and cannot do because they want to keep available resources for the next generation.”

These are more than just observations by Wendi Sia, co-founder with Sharon Yap Li Hui of Gerimis Art Project, which has published six books and another two digitally, about issues that affect the way of life and livelihood of various indigenous groups in the country.

Last month, Sia and Yap brought out Mah Meri Animal Folklore, a bilingual compilation of stories from that community. The tales were gathered from oral accounts by Julida Uju, a weaver and dancer from Kampung Sungai Bumbun in Pulau Carey, Selangor. During the launch at Sunda Shelves bookstore in Damansara Kim, Petaling Jaya, Kak Julida regaled guests with three of the stories.

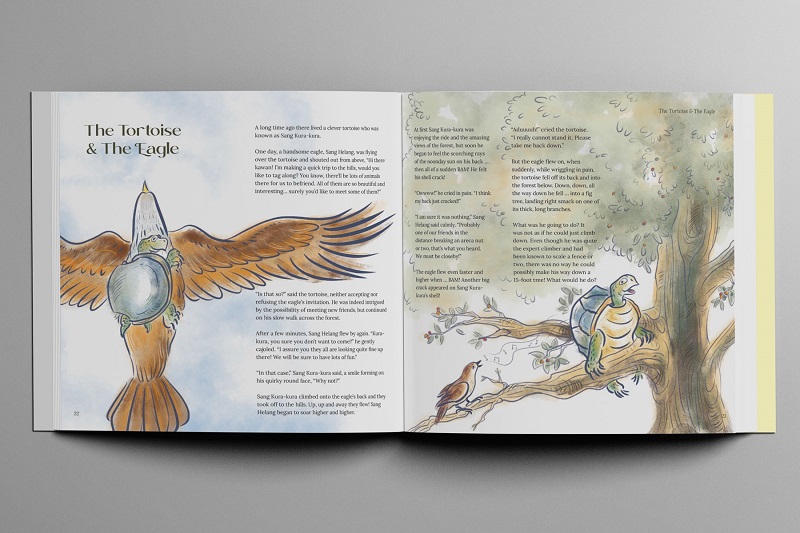

There are seven in the book, written in English by Ann Marie Chandy and then translated into Malay by Shazni Bhai, so the Mah Meri children can read them too. Tales such as The Rooster & the Deer, The Snail & the Eagle, The Squirrel & the Mudfish and The Bat & the Seven Siblings give insights into how the community lives and relates to their environment.

“Kak Julida told us they have lots of old tales about animals and the bakau (mangrove swamps). She says they used to see dolphins, sun bears, elephants and tigers. But things have changed,” says Sia, who listened and recorded the stories. She and Yap developed the idea for a book and obtained a grant from Tourism Selangor for it.

Yap did the illustrations. “The way Kak Julida tells a story is so lively, I wanted to draw something cheerful for children to look at and feel happy as they read,” she adds about her colourful, cartoon-like artwork.

Gerimis, a collective established in 2018, is “a meeting point of the cultures and voices of the forest and its people through expressions of the arts, culture and traditions”. The word means drizzle in Malay.

20230715_peo_mah_meri_animal_folklore_ms_julida_pg-9.jpg

“It’s light rain, almost invisible. It’s like saying the Orang Asli are almost invisible to people but we can still feel their presence because they are the ones who look after the forest, our natural heritage. And rain nurtures,” says Sia, a freelance copywriter.

She and freelance art director Yap were former colleagues at an advertising agency. Books and projects with and about indigenous communities in different states are something they do because “we realise there are stories in our backyard”.

Both also love nature, hence their collaborations with the Orang Asli. “The best way to protect, preserve or promote what we have is to work with them, listen and learn from how they take care of nature. They are the custodians of the land. It is something we want to push in terms of promoting their rights to their land. That is another part of the story.”

Since founding the collective in 2018, they have gone to the field and worked with various tribes: the Mah Meri and Temuan in Selangor, the Seletar or “sea people” in Johor, the Semai, Jah Hut and Batek in Pahang and the Semai and Temiar in Perak. Initially, they were observing and writing about the crafts of these groups, who slowly began to trust them with their stories.

Gerimis’ first book, Mad Weave (2019), looks at the process of harvesting pandanus leaves, processing them for weaving and the mad weave technique, referred to by the villagers as “anyaman gila” because it is fine and difficult to master. It is like a journal about master weaver Yau Niuk and her daughter Nadiawati Miah from the Kumpulan Kembang Sejambak weaving group in Kampung Paya Rumput, Sepang, Selangor. Illustrations drawn from stories about her old village, where she once planted hill paddy, reimagine the past and show how the Temuans lived in harmony with nature.

Besides drawing attention to craft making, the book also shows how things have evolved over the decades because the land has changed, Sia explains. “Where they used to live was a peat swamp forest. A lot of their natural resources to make their craft can only grow in these muddy, wet areas. Now it’s oil palm plantations. This communal story can be heard across Orang Asli villages.”

mah_meri.jpg

Yap adds that the Temuan people now make smaller versions of the huge baskets for storing rice because they do not have big enough leaves any more.

Their second book, Solastalgia: Forest, Crafts & The People, takes readers through nine Orang Asli villages along the country’s backbone of Banjaran Titiwangsa, where, through personal encounters and folklore, the villagers show the tribes’ relationship with the land and how access to resources is crucial to maintaining their culture and identity.

Gerimis’ latest collaboration is In Every Bite of The Emperor, with London-based artist and researcher Youngsook Choi and arts organisation Heart of Glass. Initiated by Choi, the long-term project explores ecological grief across communities in the UK, Malaysia, South Korea and Vietnam.

In March this year, the Gerimis team embarked on a fieldwork residency funded by British Council Malaysia, in a Semai village in Lenjang, Pahang, and then around Kinta Valley, Perak.

“We wrote about the Semai’s relationship with the river, their rituals and how they care for the spirit of the land,” Sia says. Choi’s aim is to show how, when countries were colonised, there was an extractive economy.

“When we asked the tribes why they don’t take gold or anything from the area, they say, ‘Those are things we cannot eat. They don’t belong to us and we shouldn’t take them’. They believe the gold belongs to other beings that could be in their cosmology,” Sia says.

“There is respect for nature, the ecology of their beliefs, and how the river and the land have different meanings to them. Lots of people think it’s superstition. But it’s about values and the environment,” Yap adds.

This article first appeared on Aug 7, 2023 in The Edge Malaysia.