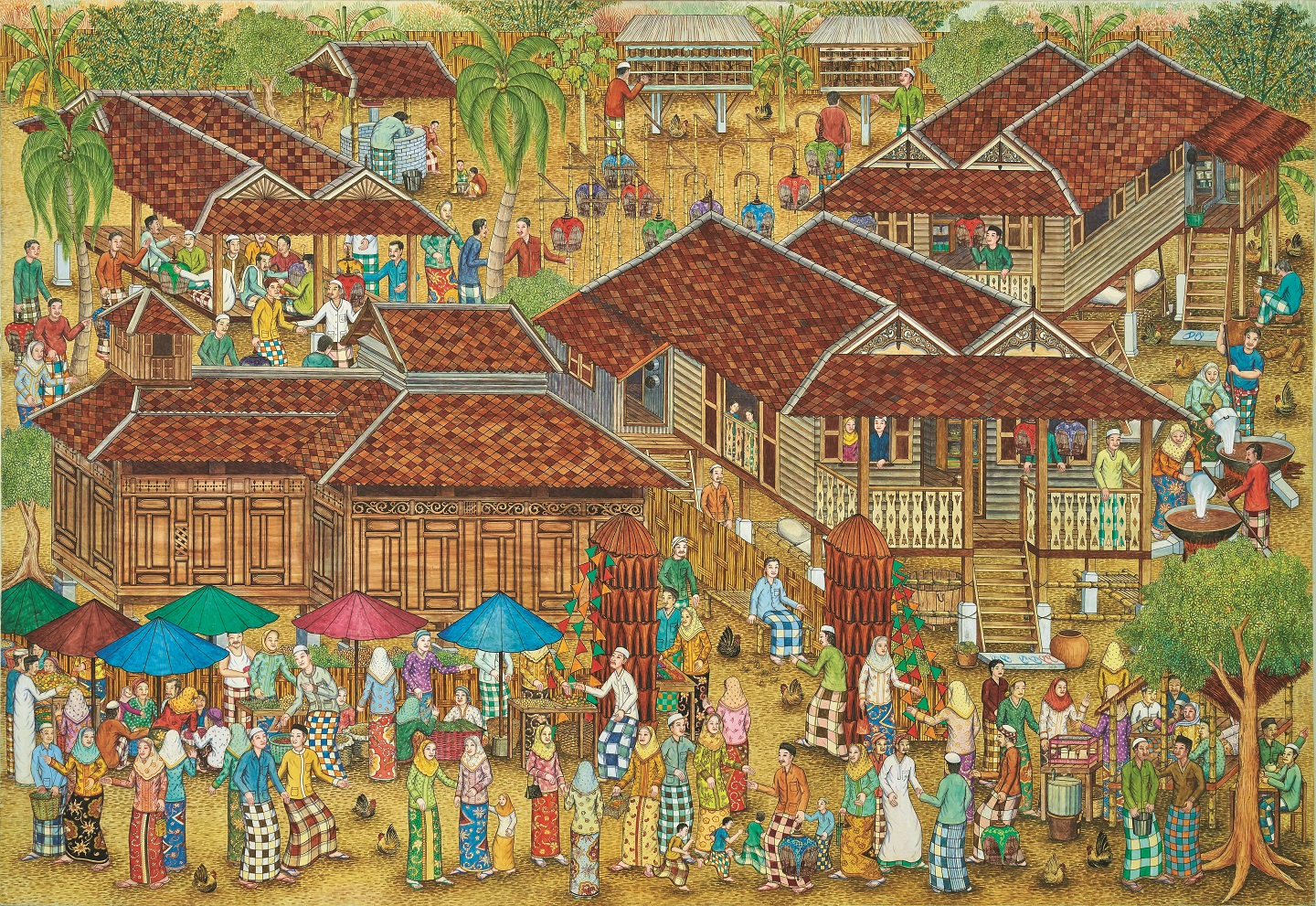

Jehabdulloh Jehsorhoh's The Way of Life of Malay Locals in the Three Southern Most Provinces of Thailand (Photo: Ilham Gallery)

The name of Ilham Gallery’s latest exhibition, Patani Semasa: An exhibition on contemporary art from the Golden Peninsula, alludes to the southern province of Pattani, Thailand. However, its focus encompasses a wider region of the deep south, including Yala and Narathiwat, which borders the north-eastern part of Kelantan.

Geographically, it is a place of interest for Malaysians, considering that Kedah, Kelantan, Perlis and Terengganu were once part of the Pattani Kingdom before they were ceded to Malaya under the Bangkok Treaty of 1909. Being a Muslim-Malay majority region, the area has seen tension and dissent against the Thai government since the colonial times, escalating after World War II when the “One Race, One Nation” policy was put in place.

But Patani Semasa is not here to sell a cause, or present a political or ideological case. The exhibition, a collaboration with Chiang Mai’s MAIIAM Contemporary Art Museum, is instead curated as a kaleidoscope offering of the cultural, humanistic and personal perspectives of the area.

“We just wanted to show the reality of the place through art. If I can use a term in contemporary art — the interest is always in presenting the unpresentable, the invisibility. And the other thing we are interested in is the untold, small narrative,” says curator Gridthiya Gaweewong.

Gaweewong, along with fellow curators Kasamaponn Saengsuratham, Kittima Chareeprasit and Ekkalak Napthuesuk, curated existing works from 28 Thai artists, some of whom are from the South. One of them is Pichet Piaklin, whose works offer a starting point for the show for those who prefer a more organised narrative.

The Buddhist Pattani native, one of the first lecturers at the Prince of Songkla University founded in 2000, is a strong influence on the artists who have since emerged from the region. Among his students are Jehabdulloh Jehsorhoh — the artist behind a veiled portrait, which is the exhibition’s key artwork — and Sirichai Pummak.

Even in their early works, one can see the emergence of a uniquely Southern perspective, one influenced by the multiculturalism of the port city’s history. The works are not unlike those of our kampung scenes. What makes them more significant is how different they are from the typical Thai paintings. Pummak’s layered works, structured in a traditional Thai mural style, incorporate scenes familiar to his home such as mosques and a military presence.

There are several Jehabdulloh works featured in the exhibition. Among them is a large work depicting the profiles of two Muslim women, with sea creature patterns created using traditional batik techniques. But it is the gap between the two faces that speaks volumes, revealing the outline of a batu nisan (Muslim gravestone) in a nod to the fragility of life.

Death is an inevitable part of many of the artworks in Patani Semasa. Another common thread that runs through most of the show is the aftermath of death — what happens to those left behind?

A painting of the wife of famed community leader Haji Sulong Abdul Kadir, who disappeared in the 1950s, is a powerful reminder of the effects of war and conflict. Another reminder is a pyramid of small containers of chili — which the public can bring home — stacked by conceptual artist Pratchaya Phinthong, who went to the south in search of photographs of the conflict but instead, found a widow who came from his hometown but is now a Muslim convert selling chilli paste alongside other widows.

In the exhibition’s only video installation, I-na Phuyuthayon powerfully interprets the idea that “life goes on” in clips showing her praying in a rubber plantation — where assassinations often happen — as well as scenes of women, whose husbands and sons were arrested or murdered, making kuih to sell.

“This is a generation that grew up around violence,” says Gaweewong, gesturing to images of guns, bullets and black-and-white portraits that surround us in one section. Most of the drawings of weapons are the works of Suhaidee Satta, a young artist from Pattani. “Satta said, ‘I cannot paint landscape.’ He just wanted to understand the violence and the core problem,” says Gaweewong. To do this, he chose to look into weapons that were often involved in conflicts, sketching the likes of the AK-47, M16A1 and M4. He was even arrested by the police once, when they found his artworks during a routine check, due to the realistic nature of his drawings and the ongoing tension in his hometown.

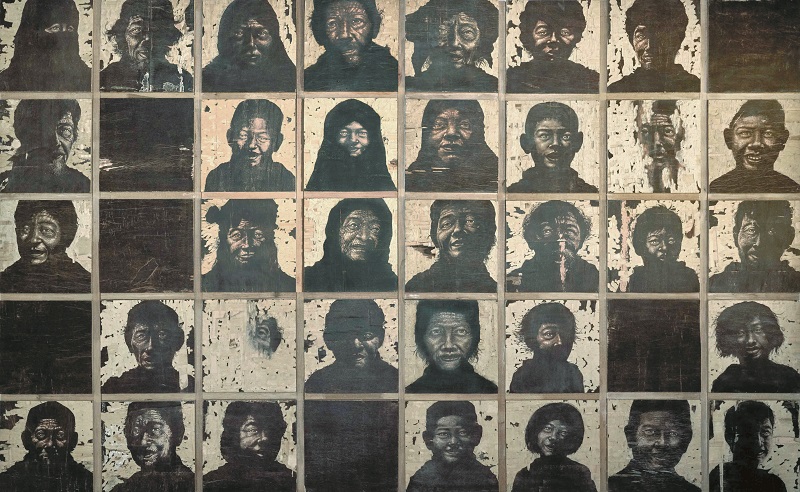

Satta’s gun models, some of which are rendered in an installation shaped like a checkpoint, are made more evocative with Anis Nagasevi’s charcoal sketches in the background — the latter portrays members of families who lost their loved ones.

This sets the tone for Jehabdulloh’s conceptual work of 89 white tombstones (the artist used soil taken from Kelantan for the installation), which commemorates the deaths caused by the Tak Bai incident in 2004. Interestingly, it is placed next to Jakkai Siributr’s black cube — which is visually modelled after the Kaaba — named 78. Inside the cube are numbers written in Jawi that are embroidered on traditional shirts, much like a tomb. The rather chilling installation also shows the difference between the official death figures and the higher number cited by locals in Jehabdulloh’s version.

A series of photographs by photojournalist Mumadsoray Deng adds context and offers a glimpse of everyday life in Pattani. The contrast of his black-and-white shots, many of which show a military presence, and the colourful scenes of people and culture, encapsulates the reality of life in the region. Artist Ampanee Satoh’s photographs of veiled women, and another series of black-and-white shots of Pattani’s iconic scenes, have the same effect.

Framing it all is Muslim poet Zakariya Amataya’s poem, printed on large white canvases and suspended at the entrance to the exhibition. The award-winning Narathiwat native’s work on identity is translated into Bahasa Malaysia and Jawi.

Patani Semasa invites us to reflect on our commonality as a region where politics and cultural identity are inseparable from religion. At least one thing is for sure, the impact of taking up arms for ideology and causes is always devastating for those who are left behind.

'Patani Semasa' runs until July 15 at Ilham Gallery, Ilham Tower, Jalan Binjai, KL.