Daerah Samar might prove to be the catharsis Jai is searching for (Photo: Shahrin Yahya/The Edge Malaysia)

In a world that is still under varying degrees of lockdown, it comes as no surprise that the inner soul yearns to break free, with dreams of vast pastures and open spaces, and memories of foreign lands and exotic faces. For Jalaini Abu Hassan, best known as Jai, it is perhaps unsurprising that his career-formative years spent in New York City left an indelible impression. After all, it was in this ultimate concrete jungle that — after winning his first scholarship to study at The Slade School of Fine Art in London, he won his second, this time to study at the Pratt Institute — he really cut his teeth as an artist amid the city’s tough, edgy landscape.

It was also in New York City that Jai discovered bitumen. “In Canal Street, to be exact,” he says, referring to the “black magic” beloved by artists, whose use of the tar-like pigment in paintings dates back hundreds of years. Theodore Gericault, for example, applied bitumen in his seminal work, The Raft of the Medusa, to realistically convey, in rich dark tones, the despair, horror and anguish of the men clinging on for dear life while lost at sea.

Jai continues: “I was a poor student, you remember, and I was passing by a hardware shop when I spotted a whole bucket of the black stuff for US$5. It was sold then for waterproofing — a byproduct of crude oil distillation; a highly synthetic, petroleum-based material … black and viscous, highly flammable. But it was also very cheap and I thought why not experiment with it, since acrylic was so expensive?”

It was there in New York that Jai learnt the meaning of survival, and how to dig deep for inspiration. “I started to appreciate the terms ‘materials’ and ‘media’. They became my true friends in the loneliness of the studio. I trained myself to appreciate alternative materials in my works. Bitumen, along with resin and bleach, were among the industrial synthetic materials that became the [key] ingredients of my works.”

Bitumen proved to be a wonderful medium, a fluid darkness through which Jai’s creative light could shine. “I knew it was the perfect alternative material for me … It offered so much potential. Of course, I had to thin it down with solvents to achieve the effect I wanted, but I also loved how you can get a tremendous range of colour that you wouldn’t get from a traditional palette. The artists in New York were already experimenting with asphalt, but when I returned to Kuala Lumpur and started showing works using bitumen, it was new and novel.”

On home ground, Jai then began creating in earnest and paying tribute to the uniqueness of the material whenever he could, from grand shows such as WIP to pairing it with charcoal in Mantera to create works of beautiful, haunting mystery and even using it to subtly outline other paintings. Now, after over a year of living through the pandemic, Jai has chosen to fully revisit his dark muse, the result of which is Landskap Daerah Samar, a title that can roughly be translated as “landscapes of vague lands”. A solo show comprising just 10 artworks, it is currently on at Segaris Art Center. Jai animatedly exclaims, “I am back to my bitumen … perhaps a grand finale after 30 years of intimacy.”

landskap_daerah_samar.jpg

Although we meet at Studio Atas Bukit — his creative hidey-hole — weeks before the pieces are completed, there is no doubt about the powerful visual impact of bitumen adorning the vast, organically shaped canvases. The otherworldly works lend itself to the imagination, of course, but Jai’s love of symbolism remains a recurring theme throughout each of them. Followers of his career would undoubtedly be aware of how the artist would almost always weave in a reference to Malay life, mythology or culture.

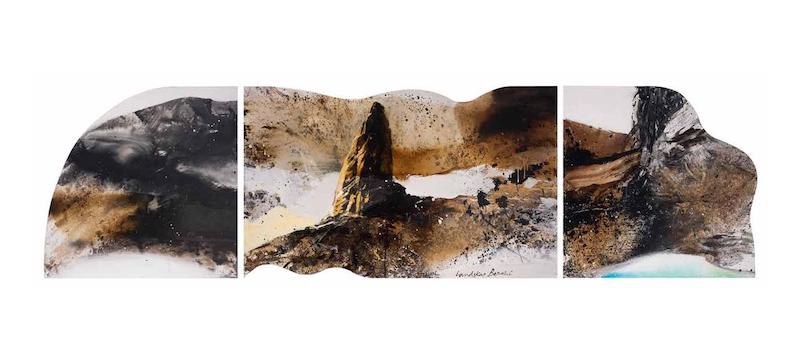

In Landskap Berahi, a fluid triptych, as well as Landskap Busut-busut Jantan, the busut (anthill) makes a comeback, having formerly appeared in works such as Putera Bunian (2010), which features a prince of a forest-dwelling spirit race, and Jembalang Busut Jantan (2018), a lithographic print on stone depicting the demon who favours the ant’s nest as his domain. Already a forbidding symbol in Malay mythology, it is also taboo to build over a busut, while the hunting of jungle fowl should they happen to be perched atop it is, likewise, verboten. There are also whispers of prayers offered to the busut at the witching hour as a means of casting spells, according to ancient black magic practices.

“A landscape painting is not necessarily a representation of a landscape”, Jai offers, “but, rather, something that, in being constructed out of fragments or echoes of representation, triggers an experience of its own — one that is somehow like an experience of nature. Daerah Samar departs from this proposition, reconstructing fragments and echoes of former representations that support an experience of their own. It attempts landscape as biography, telling the story of the very process of painting itself. Material processes have their own autonomous ways and languages.”

Another piece, the diptych Landskap Hujan Emas, directly references the Malay peribahasa: Hujan emas di negeri orang, hujan batu di negeri sendiri, lebih baik hujan batu di negeri sendiri — a proverb that translates as “Gold rain in another country, hailstones in your country, better hailstones at home”. Ufuk, Malay for “horizon”, has the unusual inclusion of a protea, a flower said to be in existence for about 300 million years, originating from the southern half of the Pangaean supercontinent of Gondwanaland. In contemporary times, it is perhaps better known for being inextricably linked to the nation of South Africa.

landskap_berahi.jpg

Its presence, so alien to Malaysia’s tropical flora, is at first puzzling, despite the flower’s obvious symbolism of beauty and resilience despite life’s unrelenting harshness. But Jai, ever the master storyteller, a penglipur lara in his own right, is perhaps telling us to look for a deeper meaning, one that references the etymology of the flower’s name. After all, the evergreen blossom takes its name from the Greek word proteus (transformation), which originated from the son of the sea god Poseidon’s love of constant shape-changing so as not to be recognised by mortals. In a way, this is a classic Jai-ism, a reflection of the artist in the canvas. The artist himself confirms it by saying, “My stylistic approach keeps changing because I believe in pushing boundaries. Without risk and challenge, the creative process would be static.

“The work requires a rigorous act of seeing, scrutinising with a microscopic and macroscopic lens. In Daerah Samar, landscape is seen anew in the light of ever-changing hyperactive modes of seeing, where virtual and actual dichotomies, contradictions and ironies preoccupy our daily perceptual routine.

“The landscape is a point of departure rather than a destination, and it begins with the visual format of the horizon and planar simulation. There is a desire to hold on to sources of abstract pictorial space/form and equally to explore the new terrain of spatial possibilities offered by process and materiality.

“These form a semblance of landscape from a distance but reveal themselves as an abstraction close-up so that, paradoxically, distance naturally pulls an image towards abstraction and sometimes towards illegibilities.”

landskap_hujan_emas.jpg

Despite obviously smashing all notions of traditional landscape works with his bitumen-coated sledgehammer, Jai insists it is not a complete deviation from the genre. “The paintings are layered with multiple planes in an attempt to dissolve the spatial relationship between figure and ground,” he counters. “Shimmering stain, translucent sepia washes created by bitumen diluted with solvent. Intermittent empty white breathing spaces randomly distributed to maximise the openness of the landscape.

“I am interested in making landscapes that insist on the artifice of painterly marks, accidental shapes, space and surface debris as constructive constituents of an image, not landscape as a bearer of resemblance. Deft and energetic mark-making, surface debris and textures are layered in complex ways to create a world where the topographical and biographical collide. Daerah Samar reflects on how we perceive the nature of abstraction and the act of painting.”

Just as nature is oftentimes depicted as a circle of life, an endless cycle of birth, survival and death, Daerah Samar might prove to be the catharsis Jai is searching for. After decades of creating with bitumen, from his return from New York to Malaysia where he was nicknamed the “King of Bitumen” or the “Bitu Man”, perhaps subconsciously he has realised it is time to let it go. “Nature is a process. Nature is not unity but multiplicity,” he muses abstractedly.

“Daerah Samar is an animating, liberating metaphor rather than a rigid interpretation of place, time and space. It looks at possibilities for play with the notion of land and space, allowing for mysterious beauty beyond physical perception. The series is defined by its attempt to create a new awareness of the association, formation and visual language that predominates the entire subject. It attempts a mode of dealing with materiality and superficiality, what is apparent rather than real.”

Yet, despite the palpable tension one detects from the phantasmagoric imagery, there is also harmony … balance. Darkness. Light. Form. Fluidity. Perhaps we got it wrong, after all. The visual energy makes clear Jai’s atman remains strong, needing just temporal release before moving on to a new body of creation. Maybe Daerah Samar is not the “grand finale” the artist alludes to, neither is it his moksha from the dark pigment. The answer could well be simple — it may be a profound homage and a heartfelt tribute to the material that helped him put down strong, artistic roots in a world and at a time when the landscape was indeed samar in his eyes.

'Landskap Daerah Samar', Segaris Art Center, Publika Shopping Galley, Lot 8, Level G4. 03 6211 9440. Until Apr 25.

This article first appeared on Apr 12, 2021 in The Edge Malaysia.