The MPO made an emotional return to live shows in early April after a 13-month pandemic-related hiatus (Photo: Malaysian Philharmonic Orchestra)

The creation of the Malaysian Philharmonic Orchestra (MPO) was more than a musical milestone. It was in line with then prime minister Tun Mahathir Mohamad’s vision that Malaysia should become “a nation that is fully developed … economically, politically, socially, spiritually, psychologically and culturally”.

Western orchestral music was, according to the post-colonial mindset, the finest form of music. And so, a foreign agency was appointed as management and operational consultants and international auditions were held for orchestral players. On Aug 17, 1998, 105 musicians performed on stage for the first time as the MPO. When the hypermodern Petronas Twin Towers was officially opened the same year, the MPO honoured the historic moment by playing a piece of European music from the 19th century — famously known as The Lone Ranger Theme.

Housed in an exquisite concert hall and flanked by the world’s tallest towers, right from the beginning the symphonic sound of the MPO was magnificent, cohesive and surprisingly mature. Equally remarkable was the concert hall itself, the Dewan Filharmonik Petronas (DFP). Warm and wood-panelled, with acoustical treatment by the world’s top experts and a Klais pipe organ with a façade inspired by angklung, it felt monumental and intimate all at once.

dfp.jpg

The MPO caused excitement in the region and earned rave reviews on tour. Over the years, performing all sorts of genres by itself and with illustrious visiting artists, there were many unforgettable evenings. To music lovers and culture mavens, it heralded a new age, the beginning of different levels of musical achievement for Malaysia.

There was only one slightly discordant note: Out of the MPO’s 105 musicians, 101 were non-Malaysians. But an academy staffed by the musicians was envisaged, to nurture local talent. Outreach and education programmes were drawn up and, among others, a Malaysian Composers Forum, music camps and collaborative projects were facilitated. In 2006, a youth orchestra was born.

There were endless possibilities, with musical brilliance right on our doorstep. And if all around the world, symphony orchestras were about stature, prestige and cultural sophistication, we were now members of that club.

Jarring notes

But outside the small circle of fans, people asked what the relevance of this music was when schoolchildren had problems with literacy, let alone music literacy. The average citizen could not tell a piccolo from a double-bass (unlike in England, say, where orchestras were common in communities and even in comprehensive schools).

Under the glitz, it seemed a step backwards, as when our history books in the 1950s taught our children about the kings of England, sidelining regional history. As time went on, the outreach programmes were criticised as mere tokenism — “cosmetic”, according to one writer. The academy never materialised, nor was there any systematic plan to grow players. (If five scholarships to conservatories had been awarded annually, in a decade, we would have enabled 50 orchestral musicians.)

Details of fees and bills, when leaked, stirred controversy. In one case, for just two performances of Beethoven’s 9th Symphony, the MPO/DFP flew in 100 singers from Melbourne instead of working with Malaysia’s many choral singers. People wrote to the press and politicians asked questions. In Parliament, Penang’s then Chief Minister Lim Guan Eng highlighted that over 10 years, RM500 million had been spent. What were the returns?

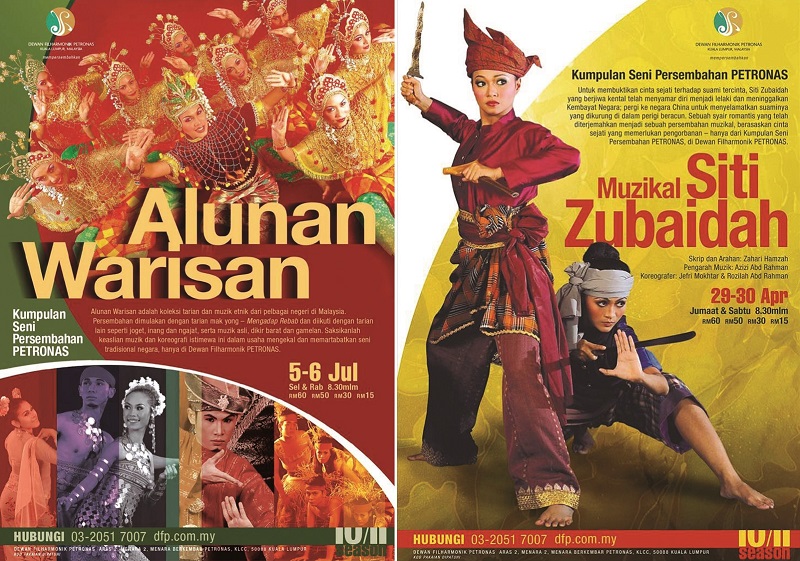

The problem was not only the size of the payments, it was the backdrop against which these were paid. Working within the same DFP was another group of musicians that played traditional music, the Petronas Performing Arts Group (PPAG). At one stage, young orchestra members were being paid nearly 10 times what senior PPAG musicians received.

petronas_performing_arts_group.jpg

After the departure of the initial management consultants, IMG Artists, and through changes in management teams and music directors, there were difficulties on the operational side too, which affected programming and planning. Petronas did not think it important to appoint CEOs who understood the classical music business. When the MPO finally landed a dynamic CEO, Karina Ridzuan, who was widely respected by the musicians in the MPO and PPAG, who brought warring factions together, created vital synergies with local artists, and in whose time the MPO’s programming began to be exciting again, she was inexplicably removed.

Gradually, it emerged that knowledge transfer was never a priority, despite the MPO’s publicised aim to “promote, develop and inculcate interest in orchestral music among Malaysians”.Writing this year, one of the original musicians said, “I do not think it was ever part of the plan to train Malaysians to be musicians; more to entice major investment to the country by showing it was as good as the West when it came to costly cultural pursuits”.

The MPO was not seriously required to develop Malaysian musical talent, any more than one’s Premier League football team should have to train the local football club or Petronas-sponsored Lewis Hamilton coach our young drivers.

In 1998, this writer asked the MPO’s music director Kees Bakels how long it would take for the stage to be mainly Malaysian. “At least 20 years,” he replied. Now, more than 20 years later, the 71-member MPO has only seven Malaysians. We are told it is because few Malaysians auditioned and, out of those, fewer still were sufficiently skilled. So much for expectations that our “world-class” orchestra would be transformative, lifting thousands of children out of musical illiteracy and into orchestras.

Meanwhile, another country with big oil reserves and children with zero music education was having phenomenal success creating young Venezuelan musicians and changing lives, using its El Sistema method and little government/ institutional funding.

mpo_group.jpg

Times have changed

Gradually, with further changes in players and management, off-stage dramas subsided, and social interaction and artistic collaborations increased. More players made friends locally and “settled in”. But the DFP’s programming for the MPO (and others) continued to lack vision. And around the world, the music was changing.

Where once the MPO was the coolest game in town, two decades on, the most exciting music was being made on laptops and streamed across the world. Malaysians’ achievements abroad — in genres as diverse as gaming music, Hollywood film-scoring and pop collaborations such as Yuna’s with Pharrell Williams — inspired and motivated music lovers at home. For music-makers, cross-border collaborations — with performances done in China with musicians from Singapore, for instance — opened up bigger worlds and de-emphasised the importance of the music scene, as it were, here.

The MPO/DFP is beset by the same woes experienced by orchestras around the world — financial, social, artistic — as orchestras become seen as cultural dinosaurs among people under 40. Although the MPO/DFP has been insulated from financial worries, declining audiences and half-filled halls have led it to devise more popular/populist events, which, for the orchestra, have both advantages and disadvantages. This should be a discussion on its own.

Re-evaluation

Throughout the pandemic, as orchestras all over the world laid off or furloughed their players, Petronas continued to fund the MPO/DFP. In July, the MPO/DFP announced that, owing to the pandemic, it was necessary for the MPO to “re-evaluate its business model to remain relevant and viable in the long run … During this transitional period, the MPO continues to explore a strategic way forward to lay the foundation for the long-term sustainability of both the MPO and the DFP”.

Despite the vagueness, some welcomed this news: a fresh cost-benefits analysis is timely, if not overdue.

The contracts of most, if not all, of the MPO musicians expire at the end of this year. Word on the street is that fewer than 30 musicians will be kept on, comprising section principals and all seven Malaysians. Auditions will be held to find another 30 Malaysian musicians, and it is hoped rehearsals will begin early next year in time for the beginning of MPO’s 2022 season in June/July. Eyes are on local players who have occasionally performed with the MPO, alumni of the Malaysian Philharmonic Youth Orchestra (MPYO) and Malaysians currently overseas.

mpyo.jpg

There is scepticism. In 1998, only four out of 105 players were Malaysians, now it is seven out of 71. The orchestra is still 90% foreign. If it took 23 years to get seven Malaysian players, how will the MPO find 30 in eight months?

The idea of an academy in which orchestra members will teach has been mooted again. Again, are there enough talents for an academy? It seems more efficient to support their studies at international conservatories, as the DFP did for pianist Tengku Irfan at Juilliard.

From standards seen in major educational institutions across the country, teaching is needed at a relatively basic level, not by way of masterclasses and occasional tuition. (By contrast, in Singapore, where musicians from the Singapore Symphony Orchestra teach at Yong Siew Toh Conservatory, entry levels are formidably high.) And while we need teachers, we do not need an orchestra in order to have teachers. Arguably, more children should be given training even if at a lower level, rather than giving a select few elite training. But this too is another discussion.

The first time round, the MPO was created from top down, with no public consultation, no talks with stakeholders. This time round, as the MPO/DFP considers the future, to make the orchestra more appealing to audiences, they would benefit by asking for ideas and input from musicians, producers, event managers, writers and others in the industry. Let history not repeat itself.

Some cynics might wonder whether the recent announcement is just one stop en route to phasing the MPO out altogether. It has been a long road. In music, “morendo” means to gradually fade out until it dies away completely. This is an alternative to a hard stop; it allows the senses time to adjust. The announcement brings to mind another by Petronas years ago when it disbanded PPAG. Petronas said it was not an end, but a new beginning, it would consider funding other music initiatives. Two years and a few grants later, that music has stopped. After 23 years, is this the MPO’s morendo moment?

mpo_stage.jpg

Alternative models

Downsizing the orchestra, accelerating its Malaysianisation, programming more popular music, requiring the principal players to teach locals — these are rumoured, on the basis that the MPO must continue. But imagine for a moment the DFP without the MPO. What music could fill it?

When the Twin Towers were launched, it was to the music of 19th-century European music. Just to cover all bases, we also rolled out onto that stage under the sky angklung, rebana ubi, serunai and seruling, tabla, nadesvaram, erhu, pipa, the usual suspects.

The tragedy is that, a quarter of a century later, if such a defining, epic occasion were to happen, we would still do the same thing.

Even now, a ministry is conducting a study on “What is Malaysian music?” That comes up regularly in the minds of bureaucrats in charge of arts funding, advertising agencies and tourism. What it is not is the angklung-rebana-erhu-tabla combo we see so often. What it is, and what it could be, is something that deserves our focus. Thanks in part to programmes such as the MPO’s Composers Forum, there are communities of composers and musicians who could take this further.

And instead of starting again with a half-new orchestra, the DFP could be home to several organically grown music groups with a proven track record and fan base, such as Geng Wak Long and Hands Percussion. Local orchestras could be involved. London’s South Bank Centre, for instance, is home to four famous resident orchestras. This would be a modest start, undoubtedly, after the glory that was the MPO, but at least it would be ours. The Singapore Symphony Orchestra had similarly home-grown beginnings (and poor reviews initially) but transcended them.

Crucial, at the top of this, is a music director who has tenacity and vision, who has studied Southeast Asian compositions and their history (both classical and modern), and who has the maturity to bring all the elements together, to form a whole that is more than the sum of its parts. This, of all, is the key task at hand.

performance_with_social_distance_seat.jpg

Why should Malaysia fund the MPO?

When the Twin Towers was conceived, with a beautiful concert hall and resident orchestra, Malaysia was at the height of an economic boom. Mahathir aspired for us to attain developed nation status and take our place on the world stage. It was not enough to have a symphony orchestra, it had to be “world-class”.

But Vision 2020 was “largely unrealised”, to quote Prof K S Jomo; the world went into lockdown and, now, we live in a different reality.

If the MPO experiment teaches us anything, it is that orchestral music is not our game. When a blog falsely announced the MPO’s closure recently, there were less than a handful of tweets about it. Trending with more than 20,000 tweets on the same day was news about a K-Pop idol. The year before lockdown, while concerts by Malay pop stars at the DFP were sold out, classical concerts were half-empty and saw the same intimate group of enthusiasts, many of them expatriates.

People make music in this country mostly with guitars, percussion, singing, bands. There is little government assistance for bands or rappers, yet an orchestra playing its rarefied form of music has had more than RM1 billion spent on it since inception.

Is music important? Yes. All the more now, as we face the darkest times many of us have known. But, across the country, our musicians are themselves struggling, calling for help.

Is the MPO important? That is less clear. It has had nearly a quarter of a century to be relevant, more “Malaysianised”, to transfer knowledge and musicianship, to create an orchestral scene and eco-system, and it did not. Should Malaysia fund it some more?

This article first appeared on July 19, 2021 in The Edge Malaysia.