Evenings of water and dense forest by Noara Quintana (All photos: Ilham Gallery)

In one of the deleted scenes in that epic marvel Apocalypse Now, the character Captain Benjamin Willard (played by Martin Sheen) finds himself at a dinner among the last relics in war-torn Vietnam, a family of French plantation owners. “When will you leave Vietnam?” the Captain asks. He receives a sharp and stern response from the heir to the homestead, “Leave? We will never leave. This is our home.”

By the turn of the century, anti-colonial stirrings began to arise from the very settings of the colonial powers themselves. Apart from revolutionary stirrings, the opposition to colonial practices in the colonies took an unlikely shape.

Preceding the anti-colonial stirrings, or pangs of conscience, was a seemingly tame, domestic novel which, in its vivid portrayals of the bestial conditions of slave life, inspired the movement towards emancipation. That novel was plainly called Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

By the turn of the 20th century, modernism and its lurch towards experimentation in creative life — combined with European ennui and a romantic turn towards the life, culture, practices and anthropology of indigenous peoples — induced a resurgence in the life of the novel, art and poetry.

In the Dutch East Indies, Dutch author Eduard Douwes Dekker, writing under the name Multatuli, composed the novel Max Havelaar, not only inspiring anti-colonial agitation in the Netherlands, but stirring the burgeoning nationalist movement led by Sukarno in what would later emerge as independent Indonesia.

Exploitation in the form of slavery was the catalyst and the plantation the setting.

The plantation with its oppressive hierarchies and subjugation, set amid the haunting setting of crop trees, served as a metaphor for social disorder and the breakdown of the individual. Experimental novelists like the Frenchman Alain Robbe-Grillet wielded the plantation experience to explore aspects of dissolution and madness.

Closer to home, the planter Henri Fauconnier peaked his novel, The Soul of Malaya, with a wild and murderous incident of amok.

The plantation as an exploration of the making of the global, of the place of the marginalised, of the centralisation of the economic model and system, but also as a place and subject for thought processes is very much at the heart of The Plantation Plot, a joint exhibition by Ilham Gallery and France-based Kadist Foundation, curated by Lim Sheau Yun, an impressive emerging curator from Malaysia.

space.jpg

Comprising more than 60 works by 28 artists and collectives, principally from Southeast Asia and the Americas, the exhibition statedly declares: “At the heart of the plantation plot was growth, progress and an open market, where monocrop commodities were planted with zeal and travelled freely across the globe. Plantations were the engine of European imperial expansion, where cash crops were produced for export, and how empires accumulated surplus wealth.

“Taking our cue from Jamaican critic Sylvia Wynter, the exhibition refigures the plantation plot as both story and place. The plot demanded large-scale human labour to tap rubber in Malaya, to harvest sugar cane in the Caribbean, to plant tea in India and Sri Lanka. Thus, it rewrote human geographies, treating people as auxiliary to monoculture and ‘planting’ them in foreign lands. Some travelled far — Tamil labourers, often indentured, were transplanted in Malaya, Guyana, South Africa. Others, such as the Huitoto and Bora natives of the Peruvian Amazon, were dispossessed and enslaved to collect wild rubber on their own land.”

It is the seemingly innocuous arc of climate, environment and product that threads this evocative exhibition and bequeaths it all the necessary intrigue which lifts it from the predictably oppositional into the experiential. A hanging stalk of Cavendish bananas by American artist Corey McCorkle at the entrance of the exhibition paves the way for a deep plotting (and digging) of the plantation experience.

body_pics_1.jpg

Perhaps the most evocative aspect of The Plantation Plot is the expansive and sensual approach to the backstory of the plantation, with its experience of marginalisation and exploitation. Even as this is recounted, everywhere in The Plantation Plot are acts of resistance and endurance. Artist, animator, film-maker and dramatist William Kentridge’s statement, “Art in a state of siege”, is also a call for response to “Even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he wins”.

One of the most intelligent and perspicacious aspects of the curator’s approach to The Plantation Plot are the subtle subversions that invoke the broader historical narrative. There are stark and painful depictions of plantation violence and exploitation. A series of paintings and illustrations, affecting the myth forging of indigenous art by Peruvian artist Santiago Yahuacarni, tells the story, passed down orally of the Putumayo Genocide, with the narration, “Norman suspended another Indian woman four stakes by her hands and feet and, after giving her one hundred lashes, he took a Peruvian flag, which happened to be handy, and tearing it to pieces and sousing it with kerosene, he wound it around her feet and set fire to it. As soon as the woman started to run off, crazed with the awful agony, he grasped his Mauser and practised target-shooting with her until he brought her down.”

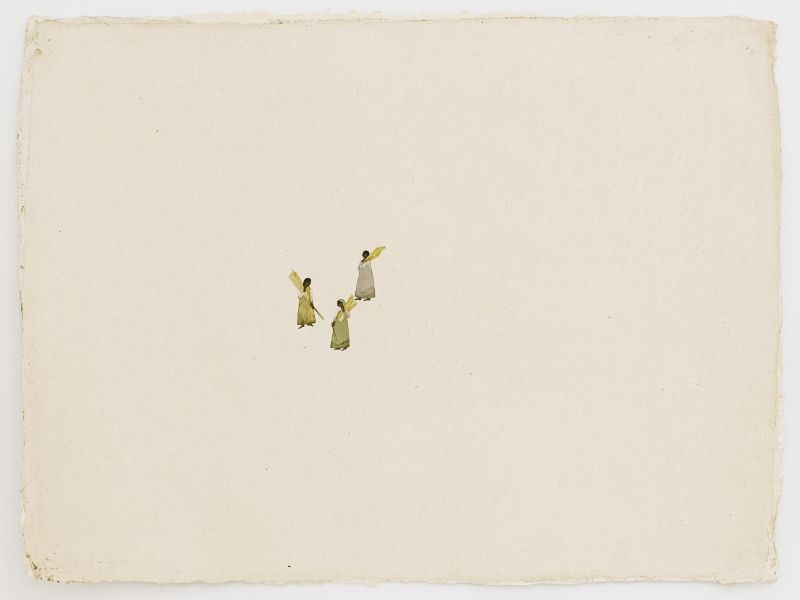

A searing and intense series of watercolours and gouaches on handmade wasli paper by Australian artist Sancintya Mohini Simpson is one of the more evocative and subversively brutal portrayals of Indian women taken to the Natal regions of South Africa to work in sugar cane and tea plantations during the age of apartheid. Complementary to this is the painting of archetype by Bangladeshi artist Joydeb Roaja, an indigenous Triupra artist, in the painting Generation Wish Yielding Trees and Atomic Tree.

Contrasting the more recent excavations into the effects — ecological, human, economic — are paintings by pioneering Malaysian artists Yong Mun Sen and Kuo Ju Ping, depicting the heroism of plantation workers and the generators of the new nation.

the_women.jpg

The Plantation Plot extends into the era of the contemporary, delving into the life of a modern nation and the very fraught and tendentious issue of land, settlement and reform, and the “exploitation of resources” that continues to bedevil the countries of the Third World, now simply known as the “countries of the South”. A particularly striking installation is by Malaysian artist Izat Arif with his soundscape “monuments” and its interrogation of the notion of Felda, featuring the voice of former US president Lyndon Baines Johnson, at the launch of Felda LBJ in Negeri Sembilan.

To embrace The Plantation Plot as another deep interrogation into the injustices and inequities of colonialism and the plantation life would be to subvert the collective culture forged by the peoples of the plantation or, in very Malayan/Malaysian terms, “people of the estate”. Even as violence and marginalisation pervade this remarkable exhibition of installations, paintings, illustrations, films and tapestries, it is resilience against homogeneity or, as stated in contemporary sociological terms, monoculture — deeper is the testament to creativeness and resourcefulness underlying the human spirit.

In 1998, Malaysian filmmaker Gogularaajan Rajendran chanced upon a collection of Tamil folk lyrics in the archives of Universiti Malaya’s Indian Studies Department. Struck by the evocative and playful nature of the lyrics, he reconstructs the songs and music with musicians in India. Coolie’s Chorus is testament to that which cannot be ebbed, captured in these lyrics:

I was born in Sithambaram

I was raised in Nanaputthur

I came to this estate

With my Chellama

Chellama, my dear Chellama

Would you like a kiss …

'The Plantation Plot' will be exhibited at Level 5, Ilham Gallery until Sept 21. Free admission. For more information, visit ilhamgallery.com.

This article first appeared on Aug 4, 2025 in The Edge Malaysia.