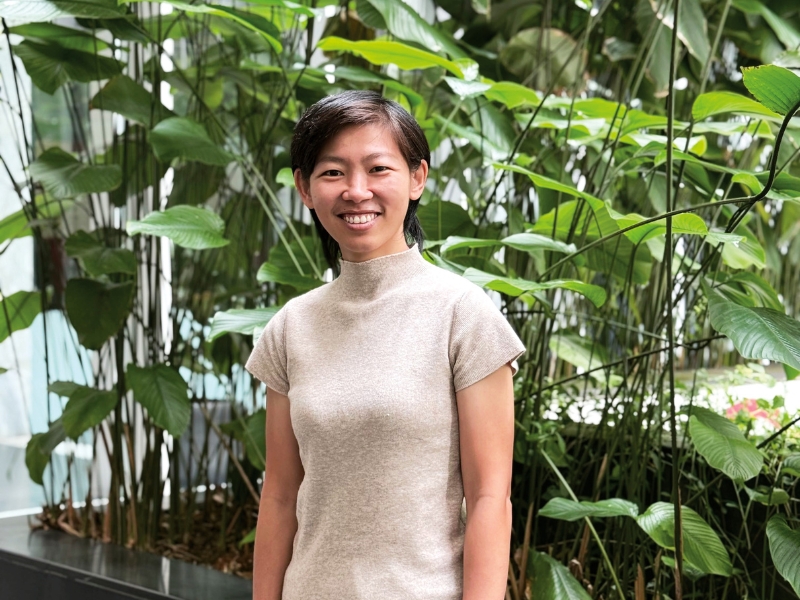

The homegrown brand, based in Jenjarom, Selangor is quickly becoming a local sensation for its authentically crafted products and inspirational story (Photo: Heritaste)

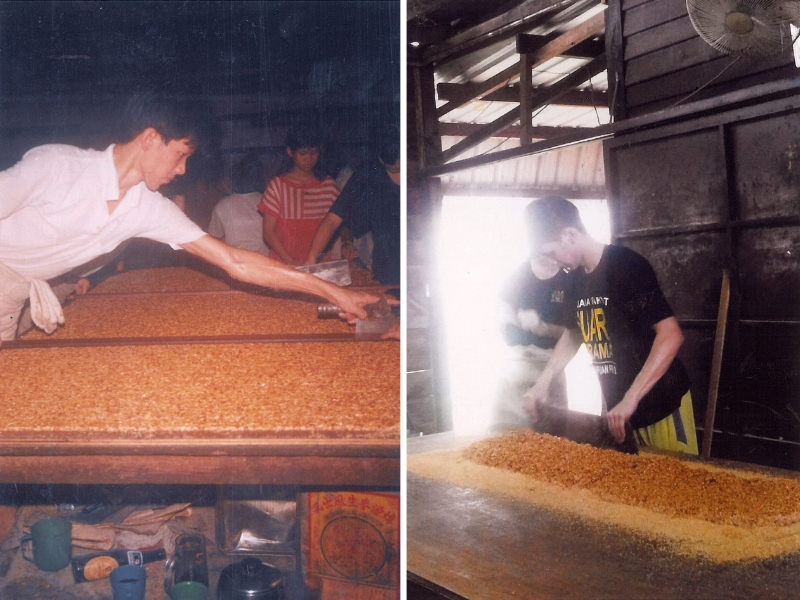

The warm scent of roasted peanuts rises from a rattling drum. A makeshift mixer, jerry-rigged from a gearbox, churns molasses into a bubbling froth. The afternoon air is still, sweet and sweltering, but the craftsmen persevere with their paddles and cleavers. Their movements are hypnotically swift, shaping and slicing pounded candy layers into little lumps to be wrapped in paper squares — they know any airflow or time wasted will cause the kacang tumbuk (pounded peanut candy) to oxidise and lose its fresh, flaky quality.

Behind a house in the small Hokkien village of Jenjarom, Selangor, a young Jennifer Tan used to study at a table while the sugary smells and sound of machines from her family’s traditional sweets business filled the home. The second daughter of five returned as an adult to fully refresh the brand’s offerings and identity in 2013, going from a humble village confectioner to what is now known as Heritaste, a rising local sensation beloved in Malaysia and beyond for its authentically crafted products and inspirational story. Aside from the kacang tumbuk and kacang pipang (sugar peanut candy), Heritaste has also created a range of crackers made from rice, almonds and pumpkin seeds, which it sells in the Jenjarom outlet and online. You may have even spotted these at several pop-up markets across the Klang Valley, where they regularly appear.

From the ground up

Now helmed by the second-generation successor, Heritaste’s origins were far from glamorous, says Tan, just the quintessential Chinese tale of an eldest son becoming an entrepreneur. “My father never completed primary school because he had to work and help support his 10 siblings. He travelled to Singapore and picked up the skills for making kacang tumbuk while there,” explains Tan.

With his own business intuition and support from other artisans in town, her father led his brothers and sisters to start producing old-school sweets out of their backyard in 1984, focusing primarily on peanut-based items.

Tan recalls how dad would cook sugar and trim candies while mum cut paper sheets and labelled packages. The neatly folded morsels were then sent to wholesalers, who would distribute them all across the country. “Watching their daily routine taught us as kids to put in effort and work hard. Even though it was just a small traditional craft, they still managed to earn a living,” she notes.

Around the mid-1990s, at the height of the business, Tan would find her schoolmates and other village youth part-timing at her family’s gong th’ng long (Hokkien for kacang tumbuk factory) for pocket money. After the turn of the century though, fast-food chains began to spring up and labour-intensive jobs fell out of favour. “By 2010, my parents were going through a period of hardship. There was still demand, but just no manpower.”

tan.jpg

The daughter’s decision to return and revitalise the business did not happen right away. “During my university days and even while working as a pharmaceuticals rep, I loved bringing these home-made delicacies to give to friends,” she says. With the foundation from her father, her co-workers would often suggest she return home to expand operations. “At the time, I would just smile or laugh it off, but I honestly had this seed planted in my mind since those early schooling days — that after all my studies, one day I could come back to help my father.”

As a statistics graduate with little to no business education though, she was uncertain how much she could offer. She initially suggested her parents plan a strategic exit if the work got to be too strenuous in their old age, since all their children had already entered tertiary education.

A family holiday to Taiwan in 2013 changed Tan’s mind.

“There, they have a lot of famous pineapple cakes and tarts, all made with a lot of passion and marketed very nicely. When I noticed the look in my parents’ eyes, seeing these vendors and the machinery they use, I felt this voice in my head asking, ‘Am I missing out on something?’. I wondered what I could do for them. I had been in a dilemma on whether or not to come back, but that little voice convinced me.”

Talk of the town

Along with her younger brother, Tan started studying traditional cooking techniques from the remaining sifus (masters), but quickly realised the lack of personnel remained a glaring issue.

“A few villagers had worked for us in the past but stopped because they wanted better prospects,” she says. Tan knew providing employees an improved environment and benefits was crucial, but given the company’s state, would take time. “I wanted this to be a platform for them to learn together. I knew if I could promise them that hope, they would be willing to come together.

“I actually went through it the tough way, just like my father did in 1984, leading his own team,” she reflects. “Because of their trust, I managed to motivate myself, even when I didn’t know how to proceed.”

It was this same loyalty to the community that stopped the Tans from shutting up shop before: “My mother asked me, ‘We have the financial capability to close, but what about the sifus who have worked with your father for close to 20 years? With their skills, if they stopped today, they might have to start from scratch in another industry.’”

old_pics.jpg

Finding people interested in such labour-intensive work can be a challenge, but is still possible in more rural areas, Tan admits. To this day, the products are made in the exact way her father did, almost entirely by hand. Each parcel of pounded peanut candy is delightfully delicate, falls apart elegantly in the mouth and exudes a refined nutty fragrance. Reaching that level of consistency and expertise is no small feat, and can demand years of dedication and effort. Tan wished to provide jobs with better prospects to the youth of Jenjarom, encouraging growth within the town rather than losing all their talents to the city, while also ensuring the survival of a fading practice.

“One of the greatest challenges has been the mindset of kampung people. I think we aren’t as confident, especially when we venture into the city and see how well developed it is,” says Tan. “But we have the spirit of sharing, and that is precious — our way of life is simpler, and we help each other. I want my staff to know even traditional candies can be professionally made and marketed, and that these skills are worth mastering. How do you make use of your time and life through crafting something? The things we make are the by-products of our team, their minds, hearts and actions.”

In 2014, Tan managed to put together a team of young individuals and moved operations from their yard to a shoplot (the site of the current store), complete with a 10ft retail space. Over the following five-year period, she prioritised stabilising the production set-up, facilitating skill transfer between experts and new hires, growing their product range and shifting to a more distinguished aesthetic that focused on the brand’s connection to heritage craft. Their signature scarlet colour channels a simpler, more traditional look, while the store’s interiors are charmingly decorated with old family photographs and tools depicting the company’s journey.

store_interior.jpg

Though Heritaste was earning a reputation by word of mouth and promotion within Jenjarom, notably during its Happy Village Committee initiative where Tan marketed their kacang tumbuk as a speciality souvenir for tourists visiting the Fo Guang Shan Dong Zen Temple, it was not until she participated in the Selangor government’s 2021 Baik Selangor competition that it gained large-scale traction.

“The programme aimed to encourage local youths to return to their villages and provide better working opportunities. [The government] conducted a series of courses convened by experts to teach participants about creating good products and stories, while offering resources to help businesses and younger generations grow,” she says.

The Jenjarom village chief, seeing Tan’s success in revitalising a traditional business, implored her to enter as their representative. “We just wanted to learn and see what we could do to elevate the business. I never thought [our proposal] would win. When they announced online that we were the group champions, that shifted the whole kampung’s paradigm. We felt really proud, and we got a lot of exposure and publicity from it.”

With this win, Heritaste’s candies and cookies garnered the attention of the local council, becoming the item of choice for members hoping to bring souvenirs to exhibitions or events abroad. The brand went the extra mile by creating custom packaging featuring landmarks from Kuala Langat in order to convey the history and culture of the district. “We used all the opportunities and channels provided by the Selangor government. Non-stop for that first year, wherever there was a market or event — big or small — we joined.”

Sweet returns

body_pics_2.jpg

Baik Selangor’s lessons in marketing, branding, photography and more proved invaluable in helping Tan push the company to the next level. Heritaste’s popularity has since skyrocketed, becoming beloved by Malaysian and foreign customers as a treat that is both perfect for gifting and which sits at the intersection between exceptional craftsmanship, traditional nostalgia and contemporary presentation. Unique boxes for Chinese New Year that incorporate dragon scales or board games, or batik-patterned gift sets, help their products stand out.

The confectioner has also adjusted its offerings to better suit modern tastes and demands: low sugar options for the health-conscious, or Oreo-flavoured kacang tumbuk for children. They also shrunk the candies to more bite-sized portions to reflect lifestyle changes through the years — people nowadays tend to work in offices, as opposed to calorie-burning manual labour, Tan points out. Beyond being consumed as a sweet snack, she notes their kacang tumbuk can also be crumbled as a topping for ice cream, salads and in popiah. (Or, in the case of one unusual customer, in a marinade for loh bak [five-spice meat rolls].)

As Heritaste continues to gain popularity, Tan has no intention of slowing down. When she took on the business, she had a loftier goal in mind than merely sustaining or increasing production. “I went on a few trips to Japan and Taiwan and realised, in all these countries, they have a representative food craft. What snacks represent Malaysia, and can we make gong th’ng one of them?”

with_sultan.jpg

Given that the brand has received permission from Tourism Malaysia to use the Visit Malaysia 2026 campaign’s logo and mascot on its products, as well as a recent halal certification, her dream is well on its way to becoming a reality.

Plus, Tan shares proudly: “We had the chance to present our candies to Sultan Sharafuddin Idris Shah of Selangor when Tuanku visited Jenjarom for the Selangor-level Chinese New Year celebrations this year. According to Tengku Permaisuri Norashikin, he actually loves kacang tumbuk a lot!”

The loyal royal repeat customer put in 60 orders for this year’s Hari Raya celebrations at the palace, and has since made a few extra purchases in past months.

“That was a huge moment for us. Baik Selangor was a turning point, which led to our recognition by the tourism boards and now the kerabat diraja [royal family]. We’ve gone from kampung to istana!” she says gratefully.

So, where to next? Tan mentions the possibility of opening new locations in the future, but what is certain is the kampung spirit at the core of the business.

“Honestly, I don’t have a very clear picture of what milestones I need to hit, but what’s more important is that I’m keeping us a learning organisation,” she stresses.

Staying up to date with modern trends, not only on consumer taste but also the digital know-how of business growth and innovation, is crucial to sustaining an olden craft in the 21st century.

“I encourage our younger team members to suggest ideas, because they are the experts on what is happening nowadays. I hope to become an avenue for them to unleash their potential. I want them to feel like they are part of something meaningful,” she affirms.

40, Jalan Intan 2, Taman Yayasan, Jenjarom, Selangor. Daily, 10am to 6pm.

This article first appeared on Aug 25, 2025 in The Edge Malaysia.