The Duchess of Windsor wearing her 1947 Cartier Amethyst (All photos: Cartier)

There are voices, and then there are echoes that never quite fade. Dame Nellie Melba was the latter. Her soprano, shimmering like champagne in crystal, resonated through the velvet halls of Covent Garden, spilled into gold-leafed salons and filled the stiff-collared drawing rooms of royalty. Although the nightingale — born Helen Porter Mitchell in colonial Australia, a world away from the Parisian parties and Viennese soirées where she would later hold court — did not grow up in grandeur, she sang with a clarity that could still an audience, including Pierre Cartier.

The youngest of three brothers and newly tasked with expanding the family enterprise beyond France, Pierre was among Melba’s admirers. If she serenaded queens and kings, he crafted the jewels that crowned them. Their meeting, though scarcely documented, was all but inevitable in such a rarefied society. She became one of the early patrons of the house, just as it began to make its mark with the Belle Époque “Garland style” — an aesthetic drawn from 18th-century French architecture and decorative arts, often featuring floral swags and bows wrought in platinum and precious gemstones.

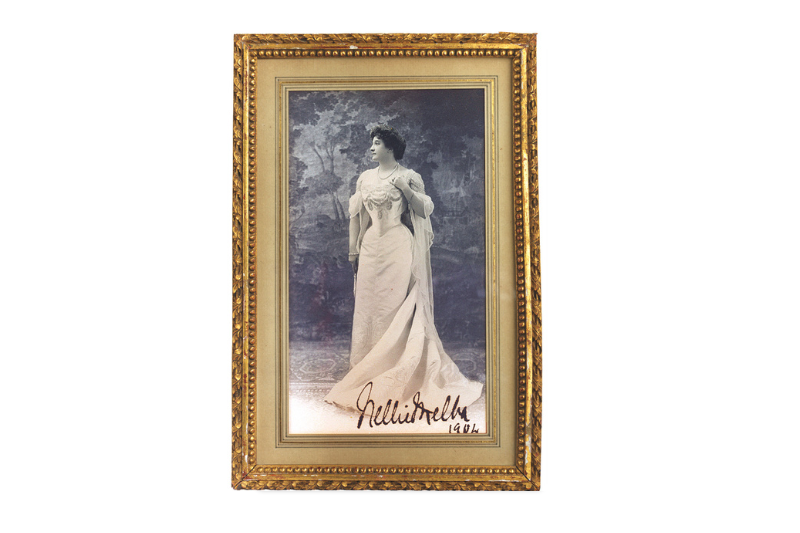

Among the keepsakes that speak of their connection is a signed 1902 photograph of Melba, a delicate yet enduring gesture of regard and respect. Once in Pierre’s possession, the memento will appear in the 2026 Melbourne Winter Masterpieces: Cartier exhibition — the most extensive display of the storied French maison ever mounted in Australia. Direct from London’s Victoria and Albert (V&A) Museum, the event gathers more than 300 exceptional creations — from tiaras and timepieces to design drawings and objets d’art — including a stomacher brooch of diamonds and pale turquoise worn by the prima donna on and offstage. Collectively, these treasures evoke an era when artistry and craftsmanship were inseparable — a dialogue that will take centre stage in the halls of the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV), presented in collaboration with Studio Sabine Marcelis and Cloud, two multidisciplinary design practices based in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

books_800px_2.png

Jewellery has always been a kind of punctuation, a means for culture to underline itself. The story of Cartier through the 20th century is, in many ways, a chronicle of how luxury learnt to shine differently. At the century’s dawn, oldest brother Louis loosened the corset on design, replacing the overstatement of status and weighty opulence of the 19th century with pieces that mirrored a new kind of woman — educated, independent, assured — who no longer needed her bling to announce her worth. By the 1920s and 1930s, that sensibility had shifted. The debutantes who danced, drove and travelled alone wanted accoutrements that could keep pace. Cartier obliged with bijouterie that moved: long sautoirs that swung, vanity cases that flashed in powder rooms and colour palettes that felt more cosmopolitan than courtly. What the brand understood, long before most, was that such finery could be conversational rather than merely ornamental.

“This exhibition celebrates Cartier’s pioneering achievements and its transformative ability to remain at the heart of culture and creativity for more than a century. We’re excited to share with visitors some of its most famous creations, as well as previously unseen objects that further enrich our understanding of a jewellery house that continues to influence the way we adorn ourselves today,” says Helen Molesworth, V&A’s senior curator of jewellery.

As Cartier’s reputation grew, so too did the circle of clients who helped shape its mythology. The Duchess of Windsor famously brought her own stones to be transformed into declarations of devotion that symbolised one of the era’s great love stories. Then came the Mexican film star María Félix, known for playing exotic femme fatale roles, who marched into the Rue de la Paix flagship boutique carrying a live baby crocodile in an aquarium, insisting it serve as the model for her next commission. What emerged was an elaborate necklace of two intertwined crocodiles that hugged the neck, each meticulously crafted to be detached and styled separately as a brooch.

7.jpg

Perhaps no relationship with the maison proved as consequential and transformative as the one within its own atelier. Jeanne Toussaint, creative director from 1933 to 1970, introduced the now-legendary panther motif at a moment when French women had yet to earn the right to vote and the social elite still clung to polite diamonds and pearls. A section of the NGV will be dedicated to this singular visionary, who attended dinners in silk pyjamas as well as turbans strung with ropes of pearls, and whose audacity set the feline on its course to becoming Cartier’s emblem and metaphor for modern elegance.

In a graceful curtsy to glories past, a designated gallery will pay homage to the ultimate head-turning accessory: the tiara. More than 20 magnificent toppers — symbolic of laurel wreaths from classical antiquity and celestial halos — will be featured alongside the grandes dames who flaunted them. For those who missed these gilded circlets during the London showing, the Australian leg offers a rare second chance to see the Scroll (1902), paraded by Clementine Churchill at the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953 and decades later, Rihanna on the cover of W magazine; as well as the Art Deco Halo (1934), inspired by ancient Egypt and owned by Her Highness the Begum Aga Khan III.

Molesworth singles out the compelling history of the exhibition’s opening showstopper — the Manchester diadem, composed of 1,500 of its owner’s diamonds. A must-see, it was made in Paris in 1903 for Consuelo Montagu, the Cuban-American heiress who became the eighth Duchess of Manchester after her husband succeeded to the dukedom.

books_800px_3.png

Beyond these crowns of splendour, visitors can look forward to discovering a necklace given to Elizabeth Taylor by her third husband and film producer Mike Todd, a 1951 marvel ablaze with diamonds and seven Burmese rubies that the actress once likened to “the sun — lit up and made of red fire”. Nearby, a diamond rose clip sported by Princess Margaret at her sister Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation is set to appear beside an array of jewels belonging to the Duchess of Windsor, including her famous Flamingo brooch; an opulent bib necklace encrusted with diamonds, amethysts and turquoise; and the 1949 Panther sapphire clip, centred on a 152-carat cabochon gem. Completing this journey will be the vibrant Tutti Frutti designs, a suite of pioneering timepieces that spotlight the jeweller’s innovations in watchmaking and contemporary works that gleam with Australian opals.

Seen together, these cultural signifiers chart the evolving politics of glamour, recounting a century of self-fashioning in which women, artists and artisans alike used shimmer — a visual rhetoric — to articulate identity and intent. Cartier’s lustre has never merely decorated history; it has preserved, and at times, rewritten it.

This article first appeared on Nov 10, 2025 in The Edge Malaysia.