Krishen Jit Fund 2025 recipients and team members at the grant award ceremony (Photo: Five Arts Centre)

The year 1971 was not a period for unbridled national idealism. Riven by fragmentations brought about by the bloody events of May 13, 1969, writers, arts practitioners, scholars and intellectuals had an urgent public role imposed upon them.

In the hallowed halls of Dewan Tunku Canselor at Universiti Malaya, the National Cultural Congress was convened to rigorously debate the idea of a National Culture — one intended to heal a fractured country and shape a shared identity to foster national unity.

The idealisation — and even romanticism — of pre-1969 culture reflected the aspirations of the immediate post-independence period. The search for a collective identity, rather than national unity; the imagining of a pristine past; the glorification of “unity in diversity”; and the idea of an extended national family following the formation of Malaysia were all encapsulated — though with few exceptions — in the naturalist and social realist art, literature and theatre of the time.

Such sentiment, even sentimentality, was later overshadowed by the events of 1969. In their wake, the National Cultural Congress emerged, guided instead by the sober spirit of “cultural nationalism”.

Whatever the attitudes towards the National Cultural Policy that emerged from the congress, the proceedings themselves were rigorous, radical and formative in exploring the cultural facets of a “new Malaysia”.

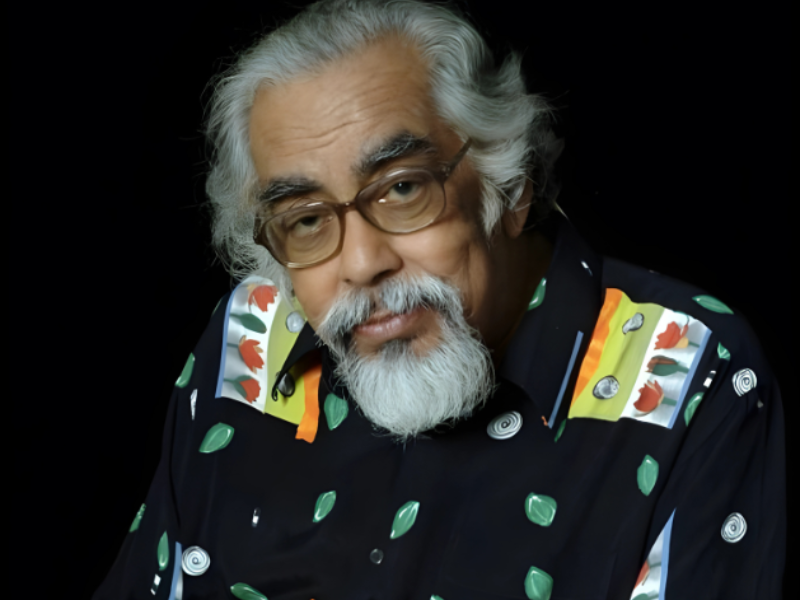

One of the congress’s key voices for theatre was Krishen Jit. Across a decades-long career marked by the twists and turns of cultural policy and practice, he remained steadfast in his vision of a theatre — and broader arts movement — that was authentically and originally “Malaysian”.

As critic and practitioner, Krishen remained exploratory and experimental, transcending boundaries that would determine and define what “Malaysian” meant. Roving, bold and boundless, his practice embraced the all-encompassing, the probing and the borderless — an aesthetic tradition that endured until his passing in 2005, notably as one of the founders of the Five Arts Centre.

3.png

Following his death, questions of continuity, lineage and legacy arose, eventually leading to the establishment of the Krishen Jit Fund in 2006. Since then, the fund has awarded grants to both established and emerging artists for projects that capture and embody the spirit of the fund — and of Krishen himself.

“[Krishen’s] ground-breaking theatre practice straddled and brought together a wide range of contrasting spheres, producing projects that were interdisciplinary, multicultural, multilingual and experimental. Negotiating between academia and practice, tradition and contemporary pop culture, Hollywood and Bollywood, the mainstream and the marginalised, Krishen’s work articulated a Malaysian identity that was ever evolving, and encouraged practitioners and audiences to reflect on their lives and societies,” the fund’s statement reads.

Marion D’ Cruz, manager of the fund and founding member of Five Arts, explains: “The fund stands as a testimony to the legacy and belief of Krishen, the company and the sponsors of the fund.

“Every year in June or July, the fund is announced, artists apply and it addressed the legacy of this man, and the legacy of giving small seed money to start a dream. The kind of grants we look for are very much in the vein of what Krishen was about — experimental and alternative work, Malaysian stories, which is very much the ethos of Five Arts as well.”

The announcement of the fund took place on April 28, 2006, at Utih … Celebrating Krishen, a commemorative event marking the first anniversary of his death. The fund was officially launched by Astro at this event.

In 2021, recognising the challenges faced by artists during the Covid-19 pandemic, the Creador Foundation significantly increased its support — enabling the fund to award 11 grants that year, a substantial rise from the usual five to six annually. From 2006 to 2024, the fund has awarded a total of 95 grants.

2.png

Earlier in 2025, Ilham Gallery held a powerful and impressive exhibition entitled The Plantation Plot, which explored the history and legacy of the plantation experience worldwide. Deftly and intelligently curated by Lim Sheau Yun, one of its “masterpieces” was a short documentary film featuring the songs of Tamil plantation workers in Malaysia.

These oral elegies and love songs — committed to the printed page but largely forgotten — were taken back to Tamil Nadu to be recorded and performed by filmmaker and artist Gogularaajan Rajendran. He has since embarked on an extensive film and documentary project on the Malaysian Tamil plantation experience, initially funded by the Krishen Jit Fund in 2021.

“My father came from the Brooklyn estate in Banting, and I wanted to make a feature film on the experience of plantation workers and their history. But I was a city boy with no immediate experience of the estate,” Gogularaajan says.

“With the grant I was able to begin my research and project, which continues to this day. More importantly, it gave me the courage and confidence to discover something that is truly hidden.”

This year, on Oct 1, the Krishen Jit Fund awarded grants to seven arts practitioners: Nadira Ilana for Sumpah Batu Sumpah (working title), an experimental video art project on the Keningau Oath Stone; Faillul Adam for Kamilah Penipu — Tapi Kami Tak Menipu (working title), a performance comprising 60 one-minute “units” voiced by Malaysians; Illya Sumanto and Wayang Women for a female-centred Kelantan wayang kulit with a ghostly folklore twist; Adriana Nordin Manan for Kubu Seni, a story lab and art incubator in Semporna focused on youth empowerment, amplifying marginalised voices and celebrating local culture; Ong Qiao Se for The Shape of an Almond, a non-fiction film about a 90-year-old woman living with Alzheimer’s disease and her last memories of pre- and post-Merdeka Malaysia; Ho Chee Jen for a project transposing gallery wall labels into public urban spaces; and Lee Yee Han for Discrimination and Visual Illusions, a hybrid performance and exhibition exploring visual manipulation in a post-truth era.

4.png

“It is very affirming,” says Adriana, whose Kubu Seni aims to develop a model storytelling lab. Centring on Semporna and working mainly with stateless children, the project explores what storytelling can truly do for young people’s expression. “And to confirm that everyone has a right to the arts,” she asserts.

The Sabah focus is also apparent in filmmaker Nadira’s Sumpah Batu Sumpah.

“Across Sabah, it is believed that if we do not abide by the tenets of oath stones, there will be heavy and violent generational repercussions,” she explains. “So, while the project is rooted in indigenous boundaries and protest, it is also an opportunity for healing and cleansing — a reminder to both Sabah and the federal government of what was promised when North Borneo and Sarawak were invited to form a nation together.”

Sumpah Batu Sumpah is an experimental audiovisual project inspired by the Batu Sumpah Malaysia — an oath stone inaugurated on Aug 31, 1964, in Keningau, which still stands today as an indigenous treaty between Sabah’s interior peoples and the federal government.

The ritual inscribed on the monolith holds deep significance — not only for the Kadazan Dusun, Murut and Rungus peoples, but also for many Sabahans collectively. “People tend to see it primarily as a political emblem, whereas I also see it as a spiritual guardian — for if not for this Oath Stone, the interior peoples of Sabah would not have agreed to Malaysia,” Nadirah says.

“For me, receiving a grant from a reputable body such as the Kishen Jit Fund means there is interest in the project and trust in my voice, which fills me with a sense of security.

“I feel that the spirit of this fund, and its namesake, resonates with my own body of work — experimental post-colonial Malaysian narratives but from a Sabahan perspective, which tends to be treated as a fringe perspective.”

The alternative, experimental and marginal as the foundations of the Malaysian spirit have endured in the imagination of the Krishen Jit Fund recipients — a spirit that Krishen himself, through his writer persona Utih, described in 1986: “I have but one wish this year, and one resolve. I would like to see a play that is engaged with the deep social and political questions of our day… Few theatre people have thought of doing theatre that will cause the audience to sit and stare at themselves. We are living in a decade of entertaining theatre, expensive theatre, professional theatre. All is promise, little has been particularly successful.”

This article first appeared on Oct 27, 2025 in The Edge Malaysia.