The book is dedicated to his wife, Wong May Lian, played a vital role in his success (All photos: Areca Books)

In order to share in Datuk Tan Boon Lin’s penchant for education, we need to appreciate the social norms that shaped the people’s outlook during the British colonial rule of pre-war Malaya, when Tan was growing up.

A key symbol of that colonial ethos was the missionary-run school, where Asian children were moulded by a band of teachers of legendary dedication and discipline into shining specimens of good breeding, ethical conduct and resourcefulness, fit for a life of public service.

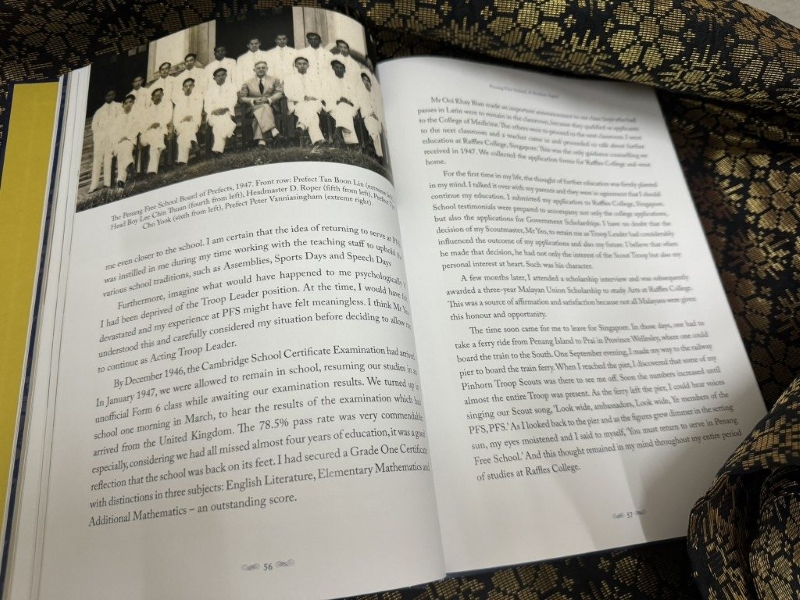

The Penang Free School, where Tan was educated, was among a select few institutions in major towns around the country that admitted the crème de la crème of the student population, giving its alumni an aura akin to that of elite British schools.

Of its many claims to fame, an obvious one is that PFS was one of the oldest English-language schools in Southeast Asia, being established in 1816. For perspective, Singapore would only be set up as a trading post by the British administrator Sir Stamford Raffles in 1819. What set PFS apart from church-administered schools was that although it was founded by a clergyman, Reverend Robert Sparke Hutchings, it was open to all children regardless of class or race, hence its name.

Tan’s life story is remarkable not just for his many personal achievements but also as an enlightening record of the historic events he lived through. For instance, the shattering of imperial Britain’s invincible image in the eyes of a student in his history class would resonate with readers in these times, when the erosion of America’s preeminence in world affairs is presenting itself in breaking headlines on our phones.

omad-4-medium-rotated.jpg

“The story of my life spans a pivotal era in the history of Malaya and Malaysia,” says Tan in his preface. “It begins with my childhood in the British Colonial Straits Settlement of Penang, during the frugality of the Depression between the World Wars, and winds its way through the harrowing experience of the Japanese Occupation, the hopeful rebuilding of a shattered postwar world, and the jubilant optimism of Merdeka. This is followed by the highly rewarding task of building a new nation. In the hope of inspiring the reader to make a difference in the lives of others, I humbly submit my personal reflections on my life, my work, my passions, my faith and my family.”

Today, when the esprit de corps that the elite schools engendered in their students has faded with the march of time, younger generations may not relate to the sentiment that made Tan resolve to return to his alma mater to teach. The emotionally charged scene that led to that decision is worth recounting, but first we must allow the tale to tell itself.

Tan’s early years were spent in Nibong Tebal, which in the 1930s was a small village at the border of Penang and Perak. In these times, when we face the breathless pace of technological change, it is quaint to encounter details like the arrival of electricity for street lighting, displacing oil lamps, in the backwater settlement.

At 11, Tan left his rural home for George Town to continue his education at PFS, which has produced a long list of stellar personalities. Historical figures like Dr Wu Lien-Teh and Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra were synonymous with the school. Dr Wu fought the Manchurian plague of 1910/11 and developed the precursor of the N95 respirator mask that became a household word during the Covid-19 pandemic, and the Tunku, of course, was our first prime minister.

Premier schools like PFS famously leave a lasting imprint on the character of their students. In Tan’s words:

“The Free School years were special to me. There was something about the school — call it ethos, atmosphere, traditions or spirit. It was the Free School mystique that changed this rural schoolboy physically, emotionally and academically, preparing him for his next stage of education.”

b2.jpg

A miraculous escape

And then there was high drama. When the Japanese army invaded the Malay Peninsula in 1941, Tan, then a mere 14 years old, narrowly survived an air raid while he was on volunteer firefighting duty. The incident left a lifetime’s impression on him.

“The siren sounded, indicating that an air raid was in progress. Soon, there were sounds of gunfire, and I realised that the fire station was being attacked by Japanese aeroplanes. Up in the tower, surrounded by the sounds of machine gun fire and the explosions of bombs, I could do nothing except crouch in fear. Bombs were raining down around me. Wave after wave of Japanese aircraft dropped bombs over the fire station, but miraculously, none hit the tower.”

Decades later, when Tan became a Christian in 1984, he ascribed his escape to divine intervention.

“...I realised for the very first time that my survival was … due to the providence, grace and mercy of God. It was God who had watched over me and protected me from the Japanese bombs and gunfire. It was entirely due to God’s grace that I had survived the bombing, and not something I had earned or deserved. Otherwise, my name would have been added to the list of air raid casualties emblazoned on the memorial plaque in the fire station.”

In 1945, when the war ended, Tan made up his mind to finish his schooling. The school was in shambles, but both students and teachers were determined to make the best of the circumstances. Besides studies, Tan had the opportunity to develop as a leader through the scouting movement and school prefectship. It was the nurturing of this leadership quality by his teachers that was to determine the roles that Tan played in his adult life.

Despite missing almost four years of education due to the war, PFS students secured a 78.5% pass rate in the Cambridge School Certificate examination, and Tan achieved Grade One, with distinctions in three subjects — an outstanding score in those times.

This paved the way for a place to study arts at Raffles College in Singapore on a Malayan Union scholarship. A moving send-off by his scout troop cemented Tan’s resolve to serve his alma mater after his studies.

“When I reached the pier, I discovered that some of my Pinhorn Troop Scouts were there to see me off. Soon the numbers increased and almost the entire troop was present. As the ferry left the pier, I could hear voices singing our Scout song, ‘Look wide, ambassadors, Look wide, Ye members of the PFS, PFS.’ As I looked back to the pier and as the figures grew dimmer in the setting sun, my eyes moistened and I said to myself, ‘You must return to serve in Penang Free School.’”

...“And return to Penang Free School I did, in October 1951, to begin my career as a schoolteacher. And then in August 1963, I returned once more, this time to take over the post of headmaster.”

Free School’s first Asian headmaster

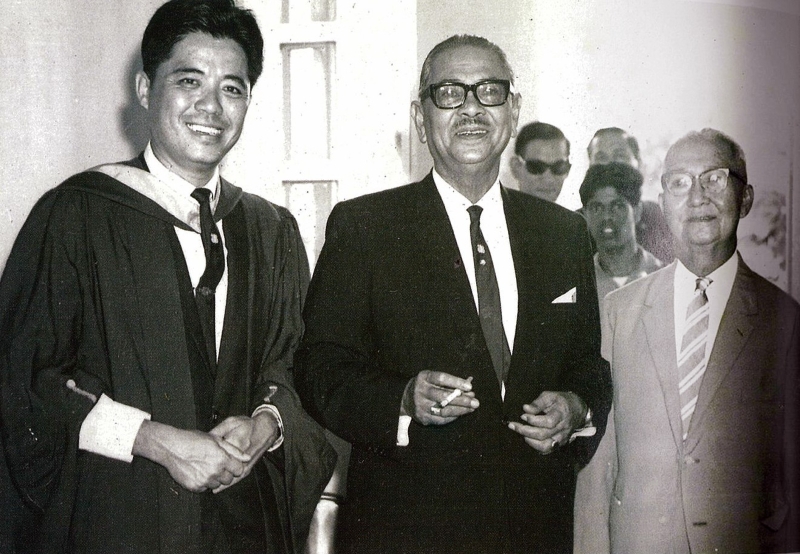

While Tan was studying for his bachelor of arts degree at Raffles College, it merged with the King Edward VII College of Medicine to form the University of Malaya in Singapore. Aiming to become a teacher, he graduated in 1951 with a general degree and diploma in education. In his words:

“Finally, in October 1951, my ambition was realised when I became the first University of Malaya graduate to be appointed a teacher at PFS!”

In these times, when business leaders with the Midas touch are much celebrated, we have to roll back the years to remember a time when the richest men in town would be humble before their children’s teachers, who not only implanted knowledge but also ethical values and discipline in young minds to prepare them for life’s struggles. This idealism would have fired the generation that Tan represents to dedicate their lives to this noble profession.

Somehow, Tan’s association with PFS, as a student, teacher and then as its first Asian headmaster, from 1963 to 1968, has that undefinable quality that is referred to earlier, which drives one to make a difference — a sentiment reflected in the title of his autobiography.

It is evident from his account that Tan made a difference in the many distinguished positions he held in his career — as education officer at the Malacca High School, headmaster at Gajah Berang Secondary, Malacca, and Sultan Abdul Hamid College, Alor Setar, and at higher levels thereafter. He served as the director of education for Pahang, then Penang, became the chief inspector of schools and ended his government service as the director of the technical and vocational division of the Ministry of Education in 1982. Tan then became director of student affairs at Tunku Abdul Rahman College, finally retiring in 1987.

Tan gives credit to his wife, Wong May Lian, for enabling his success by sacrificing some of her professional ambitions to support him at home. In a heartwarming convergence of hearts and minds, he became a Christian in 1984, finally sharing a common faith with her.

'On Making a Difference: The Joyful Journey of an Educationist' is available in Penang at the Old Frees Association and Areca Books, and in Kuala Lumpur at Kinokuniya. See here for more details.