Sanghi has worked with the World Bank for 25 years now, and has been based in countries all over the globe (Photo: SooPhye)

Apurva Sanghi hands you a die, then looks away. He asks you to turn it to a random number facing up, then cover it with a teacup. Then he stares you in the eye, and tells you it is a five. You lift the cup. He is correct. This is just one of the many amazing little feats he often performs.

To the friends of the World Bank lead economist for Malaysia, this modus operandi might sound familiar. You may have even witnessed him pull some similarly incredible moves during one of his corporate talks.

Apart from providing policy advice, lead authoring the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and offering witty economic commentary on his X account (@apurvasanghi, for those not in the know), Sanghi also performs small acts of pseudo-mentalism, something he dubs “Magic of the Mind” — predictions and up-close deductions that seem, at first blush, impossible.

But despite the psychic name, his are not magic tricks. At least, unless you consider psychology to be magic. “Human behaviour is all about making choices. We like to believe that we make them based on our own free will, but you’d be surprised,” points out Sanghi, who came to Malaysia in 2021. A microscopic shift in the pupil, a faint distortion in one’s vocal pitch — these changes would be nigh imperceptible to the average person, but he perceives them.

Deeply insightful yet remarkably humble, Sanghi does not execute his performances with any smugness or to elicit a “gotcha!” moment.

The thing that motivates him is a singular fascination with human behaviour, which informs his professional quest to improve the livelihoods in every country he works in. “My parents always told me I was, and still am, very curious, just about how things work. About why something is the way it is, what can be done to change it, and the unintended consequences.”

And while “physics was, is and always will be my first love, because I just find it to be an absolutely fascinating discipline”, he says, “I find economics even more so”. Sanghi reflects on what attracted him to the profession, what he has learned from various postings around the globe and how he channels his understanding of people into his philosophical framework.

Starting up

body_pics.jpg

Though he was born in Kanpur, in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, Sanghi spent his early years living all over the subcontinent. “When people ask me which part I’m from it’s really hard for me to say because every three or four years I lived in a different region due to the nature of my father’s job,” he remarks. “I grew up in the north, south, east, west; big cities like Mumbai and Delhi, smaller places like Guwahati, Lucknow, Indore and Bareilly. So in that sense, I guess I’m a true Indian.”

At 18, he moved to the US, attaining a twin bachelor’s degree in physics and business economics from the University of California, Los Angeles, followed by a PhD in economics at the University of Chicago (UChicago). He was also a visiting fellow at Yale University. “I might be biased, but [UChicago] is the best university for economics. Over 30 Nobel laureates in economics have come from there. I was very fortunate to have landed a seat.”

It was at this esteemed institution that Sanghi adopted his deep and holistic interest in the social science. “Physics is about modelling physical phenomena. Economics, on the other hand, models human behaviour — and that I find much more intellectually challenging and interesting. Acceleration due to gravity is 9.81m/s2 whether you are in Kuala Lumpur, Timbuktu or Papua New Guinea. But to what extent is human behaviour the same across space and time? Has it changed? How do you actually capture that in a systematic manner? And then, how do you use all this information for the betterment of society at large?” he says. “At UChicago, economics is not all stocks, bonds and interest rates, which is what most laymen associate it with. There, it is about philosophy and what makes humans think and act the way we do. It’s a combination of psychology, rational thought and philosophy.”

After some time though, academia proved all a bit too theoretical and “divorced from reality” for a personality who values real perspectives and applications first and foremost. Sanghi opted to move to the American private sector at a boutique economics consulting firm, but as “one of very few brown faces”, found it lacking. “I ended up joining the World Bank in 2000. I still remember this as clear as day: My first time walking into the headquarters in Washington, DC, and seeing the diversity of the people in their national dress. And it’s not just the visible, but also the diversity of thought. That was something I very much continue to treasure, and which has made me stay in the World Bank for as long as I have.”

Over his 25-year career with the bank, Sanghi has worked in various countries, including Thailand and Singapore in his early days, as well as the headquarters in the US, followed by three years based in Nairobi as the lead economist for Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda and Eritrea, then in Moscow before arriving in KL.

His current home here is tastefully adorned with a curated collection of artworks, photographs, statues and trinkets picked up along the way, and Sanghi does not hesitate to guide us through the stories and symbolism behind each one. Satirical sculptures packed with social criticism and paintings ruminating the fate of mortal life sit comfortably alongside family pictures and souvenirs. A figure of a frog carrying jugs searching for water, bought in Oaxaca, Mexico, critiques the impacts of climate change, one of Sanghi’s areas of expertise.

His work on various developmental topics surrounding sustainability stems from his firsthand experience of the devastating effects of pollution. In between his PhD during the 1990s, Sanghi received a fellowship to collect data and conduct research for two years in Thailand.

“This was before the Asian financial crisis, and Bangkok was absolutely booming. Traffic jams were notorious and back then I was a poor starving grad student, so I would take multiple modes of transport to get from where I lived to where I did research,” he recounts. The commute would take two hours one way on a good day, but three to four on a bad one. “I inhaled a lot of pollution, to put it bluntly. Every few months, I would actually throw up, and black stuff would come out. But that’s what got me interested in environmental issues.”

The specialisation stood at the perfect intersection between his physics background, philosophical economic stance and personal exposure to the topic. While the matter had not yet gained prominent traction at the time, it was through the support of his mentor, American economist Kenneth Arrow, that Sanghi continued to study the now incredibly pressing issue. “Bringing things back to Malaysia, we are working closely with the government to put a price on carbon. I’m really quite impressed by how important sustainability is in Malaysia. It is encouraging to see. We need every country in the world to step up and do this.”

Going global

1.jpg

While providing technical assistance and tailored policy solutions to each nation requires a comprehensive understanding not only of its economic climate but the sociocultural intricacies of the local context, Sanghi makes a point of letting new places speak for themselves.

“Nothing really readies you for living and working in these places, and that’s the beauty of it — you don’t want to be over-prepared because you want life to surprise you and your job to challenge you,” he says.

Indeed, there is often no better teacher than real experience — Sanghi recalls being shocked at the number of public holidays in Malaysia. “Even though theoretically I was aware of it, what really surprised me is the multiculturalism you see around us here. Not many countries actually have this kind of diversity. It’s something to guard, value and appreciate.”

In addition to speaking to and working with his government counterparts and others in academia or the private sector, the art lover insists that conversing with those from all echelons of society, particularly creatives and journalists, is key to developing a proper snapshot of a nation’s economic and political climate. “I go out of my way now to speak to artists because they capture the essence of a place in a very different way. A lot of the time it is satirical, and that gives you additional insight into how a society behaves. It’s a constant learning process, and in doing that you also realise how little you know. That keeps me grounded.”

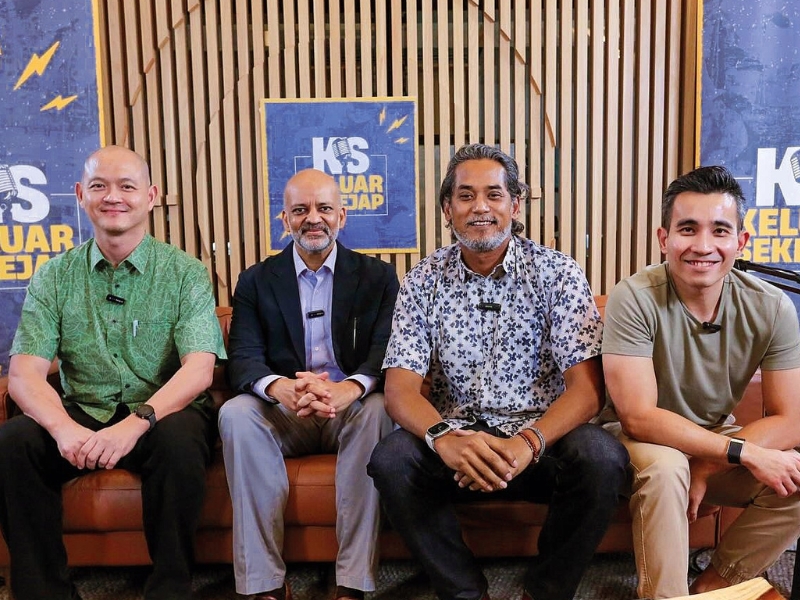

Asked what drew him here, the economist explains how Malaysia has been sitting on the brink of being classified as a high-income country by the World Bank for over 30 years. “The challenge of working to see what we can do to help the country move up and transition to high income was one of the reasons I applied,” he says. Followers of the Keluar Sekejap podcast might have seen him discussing the bank’s role and the issues facing our local economy with politicians Khairy Jamaluddin, Shahril Hamdan and Ong Kian Ming.

2.jpg

With only a few years to get a full grasp of every country, Sanghi and family make a point to travel and see as much of a region as possible while he is posted there. “The world is a dangerous place to analyse from behind a computer screen or the safety of your office. Stepping out and seeing how things work in different parts of a given country is really important for people like me,” he stresses.

“Take Russia — it’s the largest country in the world, physically speaking. Imagine if all those five years I had been sitting in Moscow trying to understand the whole Russian economy only from that perspective. Did I do that? No, I travelled all over, and that’s when you get to discover the real breadth of the lived experience.” Likewise, the Sanghis have ventured to almost all of Malaysia, from the Perhentian beaches off Terengganu to Sarawak’s Mulu caves.

Having been exposed to such varied and vibrant cultures, Sanghi has seen his fair share of the Blue Marble and its people, yet as wildly different and diverse each setting and society can be, he notes we are all nonetheless connected by universal needs and behaviours. “One overarching takeaway has been that people everywhere want the same thing. They want to have a decent life for themselves, and to provide for their loved ones — bare necessities like food, shelter and clothing, as well as aspirations for themselves and the next generation. That is consistent regardless if you are a Muscovite, Nairobian or KL-ite. The sociocultural context changes, and that’s something which makes me keep moving and sampling from this dish we call humanity.”

This awareness and reconciliation of these two truths is crucial to how he approaches economics as a study and profession. Sanghi points out that his is a field that benefits from not getting too bogged down by predictions and forecasts.

“People tend to think we’re too caught up in our models, but they are designed to capture the essence of a problem. They cannot be representative of everything in the real world. I see the next generation of economists coming to the table with large language models and moral outrage at some of the ills in society, be it about climate, conflict or inequality. It’s important not to lose sight of the basics.”

To the aspiring economists, he advises, “Instead of focusing on outcomes, try to address issues at the source. Our profession is constantly evolving, but the onus is always on the practitioners to be aware and open to incorporating these aspects of psychology and behavioural sciences. Be curious about how and why things work.”

Recognising tangible and intangible limits like money and time, and even internalised ones such as how our minds are hardwired, can be critical factors to interpreting how individuals within a society or economy function.

“There is a lot to be said about the diversity of the human experience, so trying to better understand each local context is as important as internalising the fact that on an intrinsic level we are all universal and predictable. It is the marriage of the two that is so super exciting — how could it not be?” he laughs.

Invisible hands

3.jpg

How does analysing human behaviour and studying the commonalities of people translate into a “magic” act? “It started with that fascination with why we act the way we do, both as individuals and in a group setting. It’s an interplay of psychology, probability and some tricks of the trade,” says Sanghi. None of his demonstrations are elaborately schemed or rehearsed, he notes, just a few tricks and routines he began doing around his high school and early college days. Without spoiling the outcomes, some acts involve Sanghi setting up a scenario — having someone reach for certain items or deliver a series of responses — and then unveiling a pre-written (and often correct) prediction. Other times, as with the die, he gleans a wealth of knowledge simply by reading one’s face, the microexpressions, and making accurate guesses.

One set-up involves foretelling which object someone will choose out of three. “There is nothing psychic or mystic about it,” elucidates Sanghi. “If I ask how you made those choices, you’re likely to say you did it spontaneously and without much thought. But the thing is, when we have to make decisions quickly and under ‘stressful’ or ‘uncertain’ environments, the subconscious part of your mind takes over. In this case, I nudged the reflexive part of the brain to dominate the more deliberate part. This is the stuff [Daniel] Kahneman talks about in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow. I use insights about our mind to influence your choices — only for entertainment purposes, of course.”

Sanghi adds the late psychologist and economics Nobel Prize winner was one of his mentors and a prominent influence in his life.

“Each of us is a unique individual in our own right. But, stepping back and taking a broader look, it’s remarkable how not-so-unique and predictable we can be. That is what really fascinates me. And in my current job, I have to deal with how I can harness all this knowledge towards making the world a better place in my own small way,” he says.

Just as much goes said as unsaid in a trick, conversation or exchange — everyone leaks information about themselves all the time, and even trivial knowledge can be powerful. “We understand our decisions better if we understand the people around us better. It helps us learn to make better choices, because in many ways, our choices make us.”

Rarely is it as simple as deciding someone is fibbing just because they averted their gaze. Instead, Sanghi elaborates, one establishes a behavioural baseline for an individual, then looks out for deviations from that norm. Even then, “it’s not straightforward or guaranteed”, he readily admits. “It’s about cultural conditioning in many ways. Most people think binary choices — heads or tails, nickel or dime — are exactly that, 50-50. But they’re not. If you ask most people to choose between day or night, statistically more people choose day. Left or right, people choose right. Binary choices are rarely binary.”

Knowing how each move works does not take away from the wonder of each demonstration though; rather, it only attests to how staggeringly adept Sanghi has become at observation and analysis in his 30-over years of “trial and error”. He also has a 1½-hour-long interactive talk involving psychological stagecraft about exceeding expectations, which he has presented all over the world for various diplomats, dignitaries and CEOs, designed to challenge participants’ own assumptions.

“I get everything from scepticism to trying to break it down to the why and how, to the realisation of there being something more to this,” says Sanghi about the types of responses he receives.

“The way I look at it is that every single one of us are artists in our own way. In my lexicon, the purpose of an artist is to ask questions and make other people think. [French painter] Georges Braque said it best: ‘Art is meant to disturb. Science reassures’. I like to think, in a very humble way, that I’m an artist in that sense, except my canvas is your mind and my medium is mystery.”

When he is not on the job or practising his “art”, Sanghi says weekends and free time are always enjoyed hanging out with the family — his wife Rashi, daughter (who has just left for college) and son. “At this stage of my life, weekends are about spending as much time with them as possible.” Movie nights and table tennis are par for the course, as is the Sanghis’ latest obsession, pickleball.

“One thing we have always done as a family is music, which binds us,” the dad points to the dedicated nook where a piano, several guitars and a harmonica stand ready for duty. “I dabbled in music by teaching myself but our kids are professionally trained and join their school choirs. That’s something we grew up with together. In fact, I remember when our daughter was born and we came back from the hospital, my very first act was picking her up and putting her on top of the piano,” he smiles. “We jam and sing together. It’s not the activities so much as it is the underlying motivation to spend time together, however we can.”

Generational shifts aside, Sanghi cannot help but relate to his own experience growing up. “My parents were a typical middle-class family in India, and despite all their various constraints, I think I had the happiest childhood ever. One of the most underrated things in life is a ‘normal childhood’. That’s something we try to pass on to our children as well.”

As the four-year mark approaches on his time here, Sanghi does not reveal which country is on his radar next. But one thing is for sure: “Everything is interesting about every place! You just have to have the mindset of curiosity and wanting to understand what makes the world tick. The learning never ends.”

This article first appeared on Sept 8, 2025 in The Edge Malaysia.